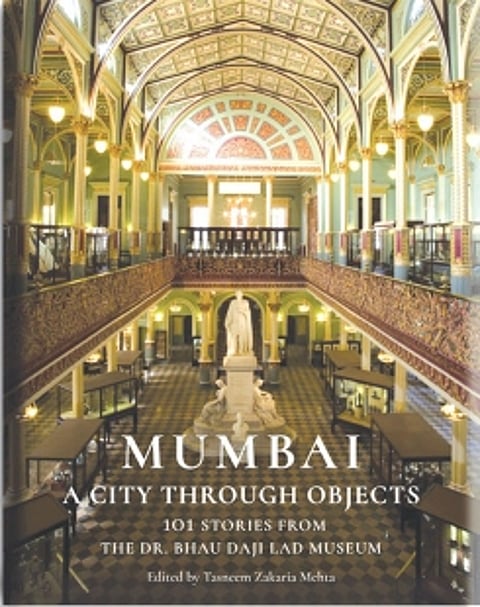

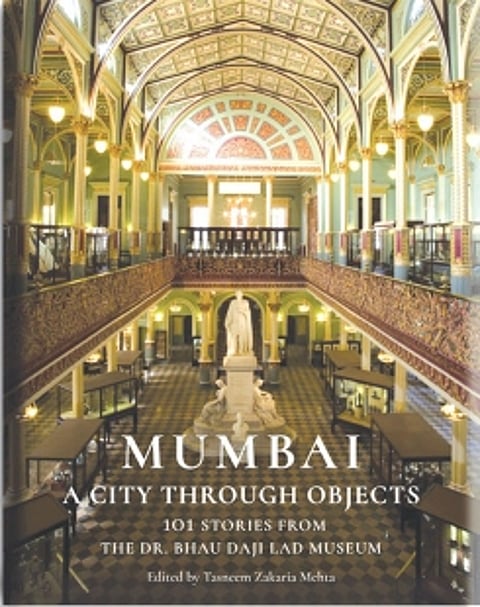

The burgeoning genre of big illustrated volumes on art and culture in India – often referred to as “coffee table books” – has an outstanding new addition. Mumbai: A City Through Objects –101 Stories from the Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum (Harper Design, Rs. 2999) has been edited with great flair by Tasneem Zakaria Mehta. It is an instantly invaluable resource on Urbs Prima in Indis, the “first city in India” that expanded explosively from isolated fragments of coastline under Portugal to the second-largest city of the British Empire (after London), and foundation stone to India’s modern identity.

Mehta has been working with that

remarkable history for many years, as main architect of the revitalization of

what was The Victoria and Albert Museum when it first opened in 1875. Renamed

100 years later, it remained fusty, hidebound, and meaningless to 21st century

audiences until she gave the old collection new wings with clever, audacious,

profoundly impactful programming. This new book burnishes and enhances that

legacy most impressively.

“Museum objects are time machines,” writes

Mehta. “They allow us a peek into a civilization long past or bring us face to

face with today’s issues, in a sense harking the future. Like architectural

treasures, objects are record keepers that reveal their mysteries as you get

more deeply engaged.”

She elaborates: “As you read the many

object stories, you begin to glean Mumbai’s evolution from a small group of

marshy islands – that the Greek polymath and geographer Ptolemy called

Heptanesia – into the dynamic powerhouse that it is today. You begin to understand

the many layers of the city’s history as the Museum shifted focus over 165

years…This is not a comprehensive history but a sociocultural reckoning.”

Mumbai: A City Through Objects wheels through an illuminative

selection of artworks and artefacts, from the famous sixth-century stone

pachyderm from Elephanta to stunning 21st century sculptures by Sudarshan

Shetty and Jitish Kallat. Mehta says her museum’s collection is “small but

unique, and bears testimony to the city’s constant renewal. It gives voice to

the vision and dynamic energy of the many people who have laboured for,

supported, or contributed in some way to the city’s making [and is] a record of

these ambitions and dreams, and the traumas of upheavals the city has experienced

on its extraordinary journey of transformation.”

With such creditable purpose, so usefully pursued, it may be

nitpicking to point to where this otherwise unqualifiedly superb book misses an

opportunity. That is its treatment of Bhau Daji Lad, whose two-page

biographical sketch – by Ruta Waghmare- Baptista – comes off as rote. We can

and should expect better from the institution named after this great pioneer,

who argued so passionately for “a temple of science containing the wonder for

ages, of Literature, Science and Art” and constantly pushed back against

colonial-era race barriers in ways that seem astounding today.

The late historian Teresa Albuquerque is much better on Lad in

her 2012 Goan Pioneers in Bombay, describing how the Mandrem-born prodigy

arrived in colonial Bombay at the age of 10 in 1822, along with his father, “a

simple painter making earthen images who hoped to make a better living in the

city.”

Albuquerque writes that Lad “studied first in the Marathi

Central School, and then attended a free private class conducted by Govind

Narayan Madgaokar, after which he gained admission to the Elphinstone

Institution” where “the Earl of Clare, Governor of Bombay, was simply

enthralled at his performance in the game of chess and advised his father to

give him a sound education.” Soon afterwards, “young Daji joined Elphinstone

College, swept off all the prizes and scholarships plus a gold medal.” From

that point, his preternatural intelligence and energy went in every direction:

Sanksrit, archaeology, numismatics, education, photography, dramatics,

politics, civic reform.

Even that laundry list is not nearly complete, because, when

already well into his thirties, Albuquerque writes “yet another avenue of study

unfolded itself to this brilliant academician with the opening of Grant Medical

College. Discarding every foreboding prohibition, Bhau Daji boldly enrolled

himself as a free student in its first batch and, along with three other Goans,

came out with flying colours at graduation in 1851. Soon after, he set up

private practice in the city, and, assisted by his brother, also reached out to

the poor and needy. He distinguished himself by operating on tumours and eye

cataracts, and even performing obstetrical surgery.” Ever the patriot, he “refused

to accept any payment from a Goan who came especially from Goa for his

treatment.”

That last line is poignant, but also highlights the hidden

history of Goa in the making of Mumbai – and by extension modern India. Thisis

incredible lore, starting with Rama Kamati, the central native figure in

seventeenth-century British Bombay, described in1670 as “so necessary for his

knowledge of all the affairs of [the city] that we are forced to make use of

him.” Later came droves of ambitious Goans seeking advancement through

education: Bal Shastri Jambhekar (the mentor to Dadabhai Naoroji and father of

Marathi journalism), Kashinath Trimbak Telang (the first Indian judge at the

Bombay High Court, and first Indian Vice- Chancellor of Bombay University), and

Dr Gerson da Cunha (the renowned orientalist researcher) amongst many others.

None of that, of course, is the purview of Mumbai: A City

Through Objects, though perhaps we can hope for greater engagement with Bhau

Daji Lad’s strand of cultural history in future endeavours from museum named

after him. When I reached out to her over the telephone earlier this week,

Mehta told me her book was meant to spark discussions to understand the past

better, but also identify directions in which we can walk together in the future:

“we have to be inclusive, give the younger generations time to grow, empower

artists to turn the tables on the colonial gaze, question and dismantle

obsolete ways of thinking.”

One

final Goa-Bombay element to this fine new book bears mentioning. It is

published by Harper Design, which is headed by Bonita Vaz-Shimray, a Bombay

Goan who has relocated to her ancestral homeland (along with her husband and

young son). When I emailed to ask whether we can make these kinds of projects

happen here, she wrote back, “Goa has a unique combination of history and

contemporary culture that appeals to the general populace, and content from

this small but significant state is bound to be remarkable given the

ever-growing creative community. For me, the homecoming to Goa after my family

left for Bombay over a century ago has certainly sparked curiosity about my

identity and roots. Artist monographs such as Antonio Xavier Trindade, his

daughter Angela; and also, Angelo da Fonseca form a critical discourse about

our colonial past and the way forward. I must commend the concept and research

in Heta Pandit’s book Grinding Stories: Songs from Goa, and I hope to see and

publish more pertinent studies in reclaiming lost tradition.”