Vivek Menezes

Here’s one of the most startling facts about our rapidly changing world: in 2023 alone, the United States caught and expelled 96,917 illegal immigrants from India along its borders with Canada and Mexico, an astonishing five-fold increase in just three years and up from basically zero just ten years ago. Now, almost unbelievably, an estimated 750,000 Indians make up the third-largest population of undocumented “aliens” in the USA, gaining fast on El Salvador (where the growth is minimal) and Mexico (from where the numbers are actually in reverse). Another highly revealing data point: the highest proportion of these desperate unfortunates are from Gujarat.

Of course, it’s not just America. Earlier this week, UK authorities reported almost 1200 Indians risked crossing the English Channel in small boats to seek asylum last year, which is 60% more than in 2022, and – again – up from literally zero just five years ago. This puts India amongst the top sources of those risking this dangerous journey, along with strife-ridden and war-torn countries like Sudan, Syria and Iraq. By contrast, there were just 103 from Pakistan. Also noteworthy: Indians supply the largest number of illegal immigrants to the UK via the more tried-and-tested - not to mention safer - route of overstaying their visas, as often pointed out by Suella Fernandes Braverman, the former Home Secretary with ancestral roots in Assagao and Calangute, whose resolute opposition on this issue is holding up the long-awaited India-UK Free Trade Agreement.

What is happening in terms of legal migration by India’s best, brightest and most qualified, who have legitimate means and avenues to leave the country? If anything, those numbers are even more shocking. According to the Organization for Co-operation and Development – the OECD is a club of 38 developed countries – India catapulted high above China as the biggest source of migrants to their member states directly after the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2020, the difference was already 410000 Indians to 230000 Chinese, and the gap has only grown wider ever since. Migrants from India now outnumber all others in a bewildering array of countries: Sweden, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

What does all this imply for those who remain in India? How should we understand “the great escape” underway all around us? I found some valuable context and perspective in an analysis by Ashoka Mody – the former IMF and World Bank executive who teaches international economic policy at Princeton – that was first published on the India House Foundation website, which says its mission is to “to empower the Indian diaspora in the United States and around the world with accurate, unbiased, and comprehensive information about the socioeconomic and political realities of India. We are committed to fostering a deeper understanding of India's challenges and opportunities among diaspora members, enabling them to make informed decisions, engage in meaningful dialogue, and actively participate in efforts to drive positive change.”

Mody says “over the last five years, 70 million Indians have sought work in the deeply unproductive segments of Indian agriculture. This is a cataclysmic regression, as anyone acquainted with the development process will recognize. A healthy developing economy—particularly one with shiny digital and physical infrastructure—should experience a sharp decline in the agricultural workforce and an increase in modern industrial and service jobs. But the Indian economy generates too few industrial or urban jobs. Outside of agriculture, the limited opportunities are in financially (and often physically) precarious construction and low-end service roles such as street vendors, housekeepers, security guards, and drivers. Hence, those seeking work are often driven to an agricultural sector plagued by declining groundwater and the weather vagaries induced by global warming. The result is high indebtedness, crop losses, and an increasing number of farmer suicides.”

He points out that “not surprisingly, the largest number of illegal migrants originate from agricultural areas in Punjab and Prime Minister Modi’s home state of Gujarat, famed for its purported Gujarat model of development. Importantly, the migrants have a reasonable standard of living by Indian yardsticks. They are from what might constitute the lower middle class rather than the poorest group—migration is an expensive business that costs tens of thousands of dollars. It is noteworthy, therefore, that Indians who have achieved some measure of success and possess a financial cushion today are, not unreasonably, worried about the future for themselves and their children. They prefer to sell their land or other assets, and borrow from friends and moneylenders to leave while they can.”

The bottom line is extremely alarming. Mody warns that “the Indian government has long since run out of ideas to create dignified jobs. Today, the policy discussion relevant to migrants revolves around reservations for government jobs (because there are too few private sector jobs) and for higher prices at which the government would procure farm produce. Both these policies seek new ways to share the pie rather than grow it. As such, they are unsustainable political palliatives. The Indian government is unlikely, therefore, to contain the demographic pressure generating the incentives to migrate.”

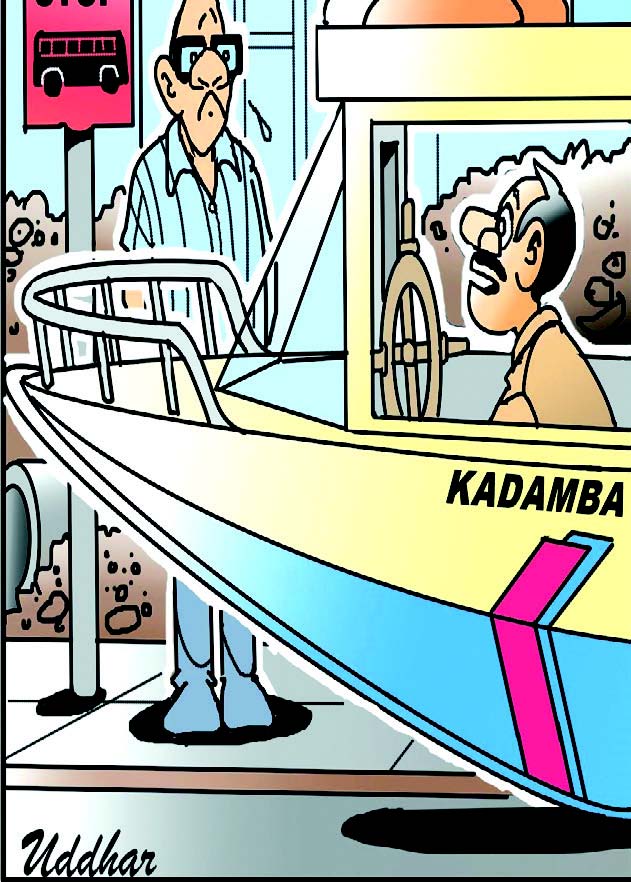

Here in Goa, even casual observers can easily perceive all the factors Mody cites are painfully prevalent except – for now – the advanced degree of anguish and hopelessness that would compel Goans to flee the country by any means necessary just like the Gujaratis. That tipping point may not be very far away, however, as India’s smallest state has been lagging behind the national growth rate since 2017. We have the illusion of development, but with very few benefits to even begin to outweigh its huge environmental, social and cultural costs. In 2021, the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy warned the employment rate – ““the total number of employed as a percentage of the working age population” – had already plummeted to 32%. That means out of every three potential employees, only one has a job. All the data after that has been steadily worse: last year the RBI ranked Goa the worst state in rural unemployment, and the Periodic Labour Force Survey of the Union Ministry of Statistics also has Goa at the very bottom, with unemployment thrice the national average.

(Vivek Menezes is a writer and co-founder of the Goa Arts and Literature Festival)