Sometimes the images streaming out of Qatar are almost too contradictory to process. Here’s only one example - just last month on October 3, the French parliament was suspended after Grégoire de Fournas – a newly elected far-right member – kept shouting “go back to Africa” to Carlos Martens Bilongo (whose parents migrated to France from Congo). After that, the National Front leader Marine Le Pen, who recently led her openly xenophobic party to its best electoral performance with an unprecedented 89 MPs, was defiant, posting on Twitter that “the controversy created by our political opponents is obvious and will not fool the French people.”

But while that ugly racism is undeniably one face of France in 2022, we saw another one altogether earlier this week on November 30, when ‘Les Bleus’ took the field against Tunisia with exactly one ethnically European player in the starting 11. All the other ten had African roots that derive from a range of different countries, while Steve Mandada (Zaire) and Eduardo Camavinga (Angola) were actually born “back in Africa”.

Of all the remarkable stories on and off the field at this year’s World Cup, above all is the narrative of globalisation, and its inevitable corollary of migration. It’s also the main story underlying global football, about which, the Switzerland-based International Centre for Sports Studies (known by its French acronym as CIES) tells us “the number of expatriate players within the teams of 135 leagues (from UEFA to CONCACAF to our own AFC) has strongly increased” over the past five years. “On the 1st of May 2022, 13,929 footballers were playing outside the country in which they grew up: +1,946 players in comparison to the same date in 2017 (+ 16%). Expatriates now represent 22% of the total number of players.”

In its 75th monthly report issued in May this year, the CIES noted “Brazil remains the principal exporter of footballers. However, after the peak recorded in 2019, the number of Brazilians abroad has fallen for the third consecutive year. Conversely, the foreign presence of nationals from the second biggest exporting country, France, has reached its all-time high in 2022. The gap between Brazilians and French has thus passed from 407 expatriates in 2017 to 241 in 2022. In the not-so-distant future, France could thus become the number one exporter of footballers.” That prediction has become reality in Qatar, where an astonishing 59 players representing 10 countries were born in France.

Those numbers are part of an unstoppable trend: 137 players – or 16% of the overall total -are foreign-born, and many others have dual or multiple citizenship, with the choice of playing for other teams. Consider the case of Tim Weah, the silky-smooth USA forward who scored against Wales on November 22. He is the son of George Weah, who is not only the only African to ever win the Ballon D’Or (which is awarded to the world’s best player) and FIFA’s World Player of the Year Award, but also reigns as the popular President of Liberia. In fact, the younger Weah was actually born in New York, but five of his team-mates were not, including Antonee Robinson (who came up through Everton’s youth academy), Sergiño Dest (formerly Ajax), and Cameron Carter-Vickers (Tottenham Hotspur).

Nonetheless, before anyone gets too cynical about carpet-bagging, migrant stars have always been prevalent at the very top of international football. Look at the very great Eusebio, for instance, who top-scored at the 1966 World Cup for Portugal, but was born and raised in Mozambique, and only moved to Lisbon as a teenaged recruit for Benfica (where we went on to score an almost unbelievable 473 goals in just 440 matches). Much less straightforward – and more interesting – examples have created overlapping, even conflicting, narratives on the pitch, such as the exhilarating, unforgettable 2018 World Cup match between Switzerland and Serbia, where Granit Xhaka and Xherdan Shaqiri drove half of Europe into frenzy after they flashed the Albanian eagle hand signal of Kosovar identity after scoring against the country which had warred brutally against their ancestral homeland.

Here it’s interesting to note that it is actually Qatar – along with some other countries - which originally forced FIFA to tighten its rulebook about switching countries. Back in 2010, the controversial honcho Sepp Blatter had declared that “if we don't take care about the invaders from Brazil, then at the next World Cups we will have 16 teams full of Brazilian players. It's a danger, a real, real danger." That was after emergency rule changes when it emerged that Qatar had offered the top scorer in the Bundesliga, the Brazilian forward Ailton, who had never even been to the Middle East, at least $1 million to come play for their country.

Eventually, FIFA clarified “the existence of a genuine link” was required between the player and the country they intend to represent, in order to prevent “nationality shopping,” In addition, players must have “lived continuously for at least five years after reaching the age of 18 on the territory of the relevant Association.”

This has made switching teams much more difficult, but not at all impossible, as Qatar has promptly proven. Its team at the current World Cup has been stacked with migrants, comprising eleven players from ten different countries. There are two Brazilians, plus Sebastian Soria, who began his professional career at Liverpool de Montevideo in Uruguay. One of the goalkeepers, Khalifa Ababacar, was born in Senegal, and the other, Oumar Barry came over from Guinea. Particularly interesting and illustrative is Pedro Miguel Carvalho Deus Correia – ecstatically cheered on as Ró-Ró in Arabic – who was born to migrant parents in Portugal, where he made his senior debut at Farense, but first played internationally for Cape Verde (his team won the 2009 Lusofonia Games). In 2011, he shifted to Doha to play for the club team Al Ahli, and then made his debut for Qatar in 2016 (for which team he has played in the Asian Cup, Copa America, Gold Cup, and now World Cup 2022).

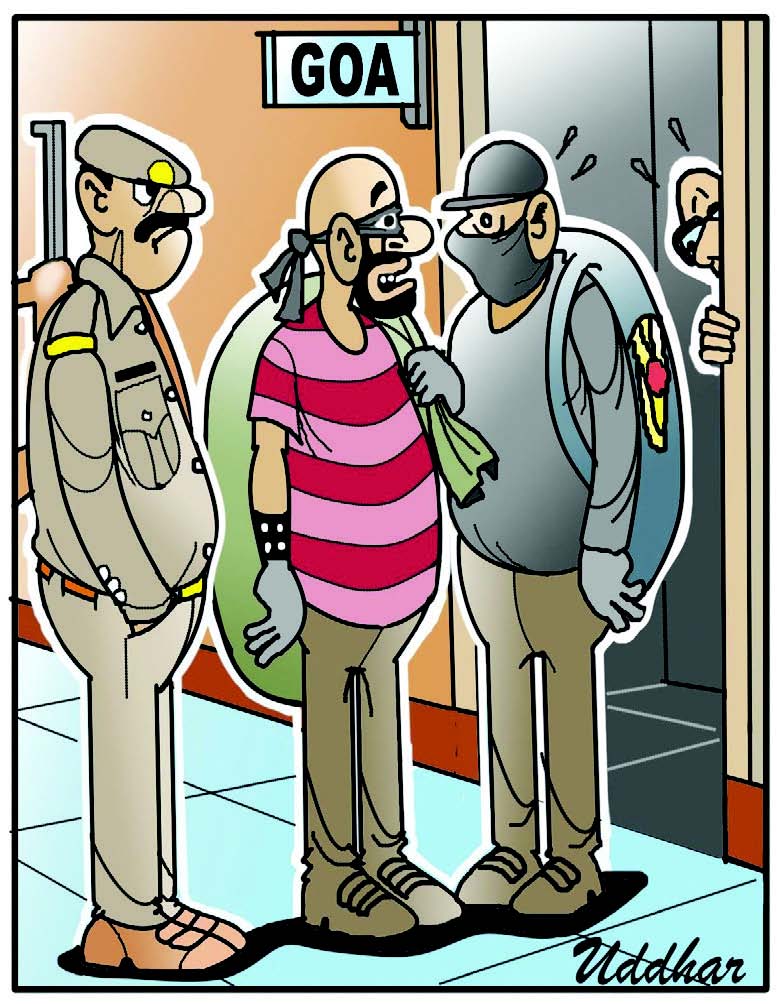

In this regard, let’s keep an eye out for Justin Fernandes, whose parents are from Goa (with roots in Assolna and Cuncolim) who is one of the up-and-comers in Qatar’s heavily touted Under-17 national team, which is headed for next year’s Asian Cup (which the country won four years ago). There’s no limit to what he might achieve in the future in the “beautiful game” as it grows more and more diverse.

(Vivek Menezes is a writer and co-founder of the Goa Arts and Literature Festival)