Shanti Maria Fonseca

With great power comes great responsibility and the Indian Constitution places heavy responsibilities on the Supreme citadel of justice. Justice Venkatramaiah was the 19th Chief Justice of India. He told journalist Kuldip Nayar on the eve of his retirement that “Contempt of Court is Not the Weapon the Supreme Court Should Wield to Preserve Its Honour”. He further stated, “The judiciary in India has deteriorated in its standards because such judges are appointed as are willing to be influenced by lavish parties and whisky bottles.” When historians in future look back at the last 6 years to see how democratic institutions have been weakened in India even without a formal Emergency, they will particularly mark the role of the Supreme Court in this destruction, and more particularly the role of the last four Chief Justices of India.

The first case of contempt in India took place on May 18, 1951, when Dr B.R. Ambedkar discussed the judgments of the Supreme Court in State of Madras vs Chapakam Dorairajan and Venkataramana vs State of Madras and, called them “utterly unsatisfactory”. The house chided him for criticizing the Apex court and Ambedkar responded: “I have often in the course of my practice told the presiding judge in very emphatic terms that I am bound to obey his judgment but I am not bound to respect it. This is the liberty that every lawyer enjoys in telling the judge that his judgment is wrong, and I am not prepared to give up that liberty”. The second took place on the silver jubilee celebration of the Kerala court in 1981, when V.R. Krishna Iyer, former judge of the Supreme Court, was invited to speak at a symposium on the ‘Approach of Judicial Reforms’’. His speech, inter alia, included the following observations. “In this country, the Jesuses are getting crucified and the Barabases are very much upheld thanks perhaps to the judiciary. Recently exposing corruption in the Apex court, Attorney General K.K. Venugopal told the Supreme Court bench of Justices Arun Mishra, B.R. Gavai and Krishna Murari that he has the names of nine former judges of the Supreme Court who have said that there is corruption in higher judiciary. I have extracts from all of them. At this point, the judges did not allow Venugopal to proceed.

Lurking beneath the court’s reasoning last week, in the way it skirts Bhushan’s voluminous charges, might we not read a tacit acknowledgement that it is quite a powerless institution? That public confidence in it is at such a low ebb that only spectacular violence of this kind can secure its foothold.

Justice Ruma Pal had summarized the contempt law when she observed that “to ascribe motives to a judge is to sow the seeds of distrust in the minds of the public about the administration of justice as a whole and nothing is more precarious in its consequences than to prejudice the mind of public against judges of the court who are responsible for implementing the law”. Those who have spent years and perhaps a lifetime as part of an institution or to study an institution may have gained legitimacy to make a thorough objective assessment of that institution. What they say regarding a matter concerning that institution should be viewed differently from a similar statement by an uninformed person. In a democratic age no institution should be beyond the reach of honest criticism. The courts are no exception. Courts should not feel elated by compliments offered or be embarrassed by adverse criticisms.

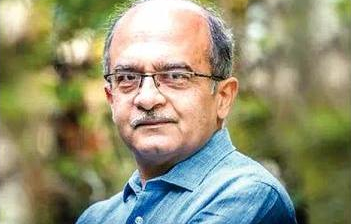

One of Bhushan’s main arguments was that criticizing courts is protected by free speech and this criticism will not amount to contempt. Further, ‘nemo debet esse judex in propria causa’ i.e. no person can be a judge in their own cause 'is one of the most fundamental tenets of justice. Yet, the apex court lacks a mechanism to follow it. Thus, from investigating charges of sexual harassment against its own incumbent Chief Justice (CJI) to deciding whether it should be within the ambit of RTI, cases are decided by those clearly affected by and interested in the outcome. On August 14, the bench held Bhushan guilty of making ‘scandalous’ and ‘scurrilous’ comments against the institution of the Supreme Court.

Recently the Supreme Court imposed a fine of Re 1 on activist-lawyer Prashant Bhushan after holding him guilty of criminal contempt of court for the two tweets against the Apex Court and Chief Justice of India S.A. Bobde. The same court was a silent spectator to incessant mudslinging a couple of months ago against Justice Madan B. Lokur, one of its own retired judges. What were the courts key arguments with regard to the alleged contempt of Bhushan: it relied on Brahma Prakash Sharma (1953) in which case a Constitution Bench held that it is not necessary to prove affirmatively that there has been actual interference with the administration of justice, and it is enough if a defamatory statement is likely, or tends in any way, to interfere with the proper administration of justice. The bench also relied on C.K. Daphtary (1971) in which case the court held that "We are unable to agree with him that a scurrilous attack on a judge in respect of a judgment or past conduct has no adverse effect of undermining the confidence of the public in the judiciary". Bhushan's tweets could never truly 'shake' the confidence of the Indian public. Unfortunately, it was already and irretrievably 'shaken' from the start and has never really stopped. His tweets were not intended to malign the Apex court or the CJI but only offered constructive criticism. Alas! If only the Apex Court could have handled this matter with more grace and equanimity.

(The writer is a social scientist and practicing criminal lawyer).