RACHEL FERNANDES

SIOLIM: It is 4.30 am in the

riverside village of Ribandar. Not a soul can be heard, save for the odd stray dog.

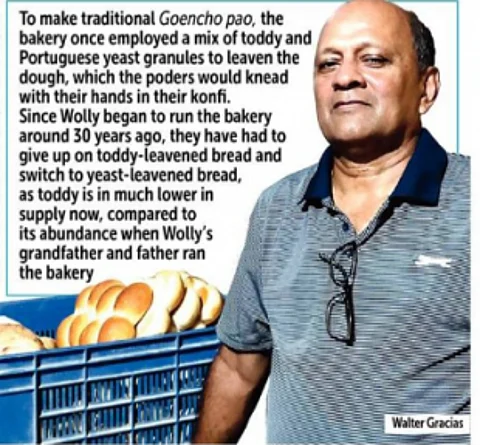

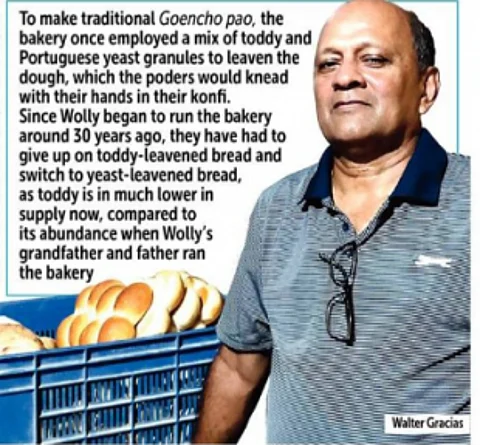

While the village soundly sleeps, in the recesses of the erstwhile palace of the Viscount of Ribandar, Walter Gracias is hard at work executing an art he has perfected over nearly three decades - the magic of breadmaking. Walter a.k.a Wolly, an accomplished State-level footballer in his youth, was handed down the management of the bakery from his father, who in turn took it over from his own father and Wolly’s grandfather, Frederico ‘Fidelis’ Gracias, who gave the bakery its name - Fidelis Bakery.

Fidelis Gracias, a resident of Cansaulim, purchased the former palace sometime in the late 1930s and converted the Viscount’s horse stables into the present bakery. Alongside his bakery, this enterprising gentleman was the brains behind many a side hustle; from running a flour mill, to selling firewood, to producing coconut oil the traditional way (by manually drying coconut kernels in the sun), right to selling the leftover husks of the coconuts he’d extracted oil from, as kindling. It didn’t just end there, he even found the time to rear his own herd of pigs who would be fattened up on the unsold stock of bread of the day, to end up becoming the contents of sausages and feast day roasts for the surrounding villages.

Fidelis split the management of the bakery amongst his three sons, who each ran it for four months a year.

Wolly fondly recounts the time in his childhood when he developed an interest in his family business. As a young lad, he would be roped in to help his grandfather knead the dough to prepare the most sought-after evening tea time delicacy of the day; panke. The now-extinct cupcake-shaped sweet breads, flavoured with jaggery, grated coconut and sesame, would be sold door-to-door in a small basket, by a poder on foot.

Life at the bakery has changed since his grandfather's time, when the poders at the end of their four-month tenure would bake and distribute Poderacho Bol among their patrons as a gesture of gratitude for their patronage. Poderacho Bol is not your average deep brown

bol, but a large, light brown coconut cake - big enough for a small family to savour at tea time, explains Wolly's wife, Vaniza. Though Wolly’s poders no longer prepare Poderacho Bol, Wolly welcomes me with piping hot katre pao slathered with luscious Amul butter and sweet tea served in dainty vintage cups from Vaniza's enviable collection.

I point to a massive rectangular, trough-like vessel, which Wolly explains is a konfi; in which dough was hand kneaded during his grandfather's time. He tells me how, back in the day, the dough kneading would start at 5.00 pm the previous evening and the process would end at 5:30 am in the morning, following which the poders would head out to sell their bread by foot, with a dando (a tall stick) in tow. Selling bread was a delicate balancing act, where the poder would have to balance his massive pantlo of pao over the dando, which would be firmly planted onto the ground. Back then, they would only supply bread in the morning. Today, the dando method is long defunct. Now, they supply bread twice a day, in the morning and in the evening, with their pantlo firmly tied to the back of an Atlas cycle.

I watch as his workers fashion poies out of a massive heap of dough. He tells me the original recipe that was in use till his father’s time consisted wholly of wheat, but he has adapted the recipe to use a mixture of refined wheat flour and wheat bran.

I ask Wolly what the term “Goencho pao” means, in response to which he tells me about the toddy-fermented pao of his predecessors’ time. Back then, toddy was plentiful in supply and would be home-delivered to the bakery by the toddy tappers of Merces. Wolly tells me that the bakery employed a mix of toddy and Portuguese yeast granules to leaven the dough, which the poders would knead with their hands in their konfi. Since he began to run the bakery around 30 years ago, they have had to give up on toddy-leavened bread and switch to yeast-leavened bread, as toddy is in much lower in supply now. Wolly has been baking with yeast ever since he took over the running of the bakery three decades ago, of which he carried on using the konfi for the initial 10 years, before moving on to a dough mixer around 20 years ago.

And what of his behemoth of a wood-fired oven? Wolly’s wife, Vaniza, tells me the oven was commissioned by Fidelis when he purchased the house and its wood-fired core blazes bright to this day. During the eight months he isn’t managing the operations of the bakery, Wolly is somewhat of a celebrity in certain circles. A passionate singer, who discovered his talent for singing during the Covid-19 pandemic, he is the headliner at River Isle Restaurant opposite the Divar Ferry in Ribandar.