Vivek Menezes

Back in 1980, the Goa government took down the striking statue of Luís Vaz de Camões that had been put up in Old Goa in the last gasp of the Estado da Índia just 20 years earlier, and sent it to its current home at the ASI museum nearby. The decolonising sentiment was and is perfectly understandable, but in this case it was a historic mistake which merits reversal. While it is true Portugal celebrates the continent-hopping 16th century poet as their national icon, his work belongs to India just as much (and perhaps even more). As the late, great poet and translator Landeg White – author of the authoritative Oxford World Classics edition of The Lusiads – often summed up, Camões was “made in Goa.”

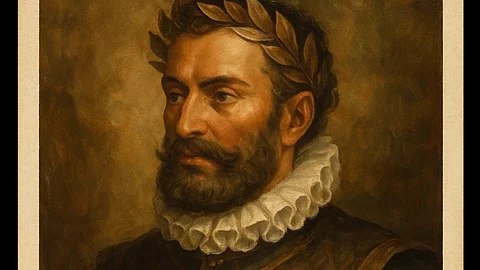

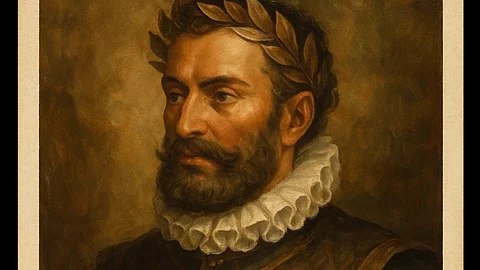

White’s insight is essential context with which to view the ongoing group art exhibition ‘Os Rostos de Camões – A Celebration of 500 Years of the Global Poet’ at the superb heritage premises of Instituto Camões in Panjim. Here, just steps down the Mandovi riverfront from the Institute Menezes Braganza, with its masterpiece azulejo entranceway depicting key verses from The Lusiads, an excellent selection of Goan artists under the curation of Dr. Savia Viegas has delivered several thoughtful and thought-provoking artworks based on the poet’s relationship with India. I especially liked the brilliant painting reproduced on this page by the 50-year-old veteran Vitesh Naik of Margao, who told me he depicted Camões with an Om pendant to “symbolise the cultural exchange and spiritual exploration he might have experienced during his 14 years of stay/exile in Goa, reflecting blending of cultures and ideas.”

Via email many years ago, Landeg White (who was Lisbon-based for the latter decades of his life) surprised me with an original poem of his that I have not seen reproduced elsewhere, in which he expressed an empathetic understanding of the protestors who pushed Camões off his Old Goa pedestal: “The Portuguese, too, had made Camões/ unwelcome, this convict soldier/this perennial poet-jailbird, who/ clutching that same manuscript/ had fled the Inquisition’s flames/ His epic celebrates a globe, abundant/ in people and fruits, now navigated.” Then and now, those lines are a pertinent reminder that the “national poet” celebrity status occurred only posthumously, after a lifetime stuck on the fringes of respectability amid myriad humiliations. In Goa, for example, he spent a good amount of time languishing in jail.

Camões was only 25 when he left Europe, as White recounts in his introduction to the Oxford edition of The Lusiads: “The previous June [1552] during one of Lisbon’s biggest religious festivals, the Corpus Christi procession, he had fought a duel with one Gonçalo Borges, keeper of the King’s harness, and wounded him with a sword thrust. He was jailed in Tronco prison, and released on a payment of a fine of 4000 reis and an undertaking to proceed to India as a common soldier…it was in India that he became a great poet, the first European artist to cross the equator and experience Africa and India at first hand. The result is The Lusiads, an epic of European thought and action in the sixteenth century.”

It is impossible to overstate the importance of Camões and his verses to Portugal, its language and identity – even more central than Shakespeare to England and the English, or Dante to Italy and the Italians. Like those two, he substantially shaped both the modern language and literature, with the added contribution of substantially crafting modern Portuguese identity itself. White says “during his years in India, Camões ‘discovered’ two things. First, he learned what it was to be Portuguese, to come from a landscape whose towns and rivers he loved, whose plains and castles were haunted by the ghosts of warriors who had fought for this territory, whose provinces were part of Christendom and the Holy Roman Empire but were emerging as a ‘state’, and whose people were learning loyalty to a concept of nation which transcended loyalty to kings. Secondly, he learned to celebrate what the Portuguese had given to the world with the pioneer voyages of the fifteenth century, culminating in the voyage to India, in revealing the planet’s true dimensions, its wealth, and its multitudes of peoples. It was the former of these ideas which was prophetic, taking wing after the restoration of Portugal’s independence from Spain in 1640. The latter, Camões’s celebration of the newness of the world, was a theme that required, and requires, constant rediscovery.”

That quote is from Camões: Made in Goa, a stunning little book written by White as an explicit gift to India, where he expands upon a case he started to make after his first joyous visit to the subcontinent for the 2012 Goa Arts + Literature Festival, and then wrote about the following year in an essay entitled Camões de Goa for an anthology I edited for Semana de Cultura. Those lines came racing back to my mind at Instituto Camões this week: “Is Camões a poet for contemporary India? It’s up to you whether or not you want to claim him, but if India can take on Kipling, at least selectively, then Camões should pose no problems. He spent 15 years in Goa and beyond, plus a further two or three in Africa. They were the best years of his adult life, during which he wrote much of his greatest poetry. As I have argued, it was the experience of being in India that changed him from being a conventional court poet into one of the most original poets of the period. This is not something the Portuguese will ever have told you. He is revered in Portugal as the national poet. But it’s not good for a poet to be worshipped. It gets in the way of seeing him clearly and taking the real measure of his greatness. [The real] Camões, in rags and in jail, is a figure they turn from in embarrassment. It is an image for India to embrace."