Caste remains one of the most visible and influential social structures in India, impacting nearly every aspect of life—from employment and education to customs, dietary habits, and interpersonal relationships. Though caste is largely hereditary, it is not entirely static. Through shifts in practices or marital alliances, some caste groups have historically altered their social standing.

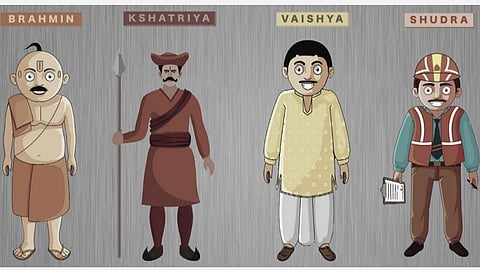

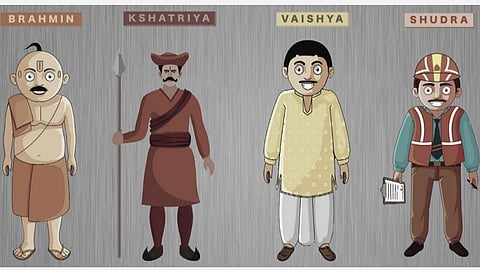

At its root, the caste system traces back to the varna framework of the Vedic period, which classified society into four broad hierarchical groups based on perceived purity and pollution: Brahmins (priests and teachers), Kshatriyas (rulers and warriors), Vaishyas (traders and agriculturists), and Shudras (manual laborers and service providers). A fifth category—Dalits or Scheduled Castes—fell outside this hierarchy and was historically often subjected to severe discrimination.

Over time, the varna model merged with the more localized and complex jati system, which now comprises over 3,000 castes and 20,000 sub-castes with regional variations and social rankings. The term “caste” itself was introduced by the Portuguese in the 16th century, derived from their word “casta”, meaning “lineage” or “breed.” It was used to describe the rigid, hereditary social divisions they observed in India. The English adopted the term from Portuguese, and it has since become a standard reference to India’s system of social stratification.

Brahmins were regarded as the embodiment of knowledge and spiritual discipline. Revered for their renunciation of worldly pleasures, they were believed to live in constant contemplation of the divine (Brahman). Serving as priests, teachers, rishis, and scholars, they led a life of celibacy and austerity. Even married Brahmins were considered 'Brahmacharis' if they remained detached from physical indulgence, engaging in intimacy only for procreation.

Significantly, the Brahmin status wasn't exclusive by birth—individuals from other Varnas could attain it through rigorous learning and self-discipline. Traditionally, Brahmins were entrusted with educating the youth of all Varnas, ensuring continuity of ancestral wisdom through the guru-shishya (teacher-disciple) tradition. While primarily dedicated to spiritual pursuits, some Brahmins took on roles as warriors, merchants, or farmers during times of adversity.

Marriage norms allowed Brahmin men to marry women from the first three Varnas, though marrying a Shudra woman could diminish their priestly privileges. Brahmin women were respected for their chastity and moral strength, with scriptures like the Manu Smriti prescribing that they ideally marry within their Varna, though some flexibility was permitted.

Kshatriyas: The Warrior-Rulers and Protectors

Kshatriyas formed the ruling and military class, tasked with protecting the kingdom, upholding justice, and administering law and order. Their training encompassed warfare, statecraft, ethics, and penance. Like the Brahmins, they received early education in ashrams under spiritual teachers to build a foundation of moral responsibility. Kshatriya women were not mere consorts; they were trained in warfare, capable of governing in their husbands’ absence, and often took an active role in defending kingdoms. Maintaining the purity of royal lineage was crucial for preserving dynastic authority. Inter-varna marriages were allowed for Kshatriyas, though alliances with Shudras were less preferred.

Vaishyas: The Economic Backbone

Vaishyas were responsible for agriculture, trade, and commerce. As a “twice-born” Varna, they also underwent spiritual initiation and education. Cattle rearing was especially esteemed among Vaishyas, reflecting its economic and religious importance.

Collaborating closely with Kshatriya rulers, Vaishyas contributed to wealth generation and improving living standards. However, due to their proximity to material wealth, they were often viewed as susceptible to ethical lapses—prompting strict oversight from rulers.

Vaishya women played an active role in family enterprises and had legal rights over property. They enjoyed significant personal freedoms, including remarriage, and were expected to help raise children alongside their husbands.

Shudras: The Essential Service Providers

Shudras, though positioned at the base of the Varna hierarchy, were vital to the functioning of society. Traditionally assigned service-oriented duties, they supported the Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas in various domains. Despite widespread belief, certain scriptures like the Atharva Veda and Mahabharata allowed Shudras to study sacred texts and attend ashrams.

Unlike other Varnas, Shudras were not subject to the sacred thread ceremony. While Shudra men were expected to marry within their own Varna, Shudra women could marry into higher Varnas, though this had social limitations.

Over time, many Shudras took up farming, trading, and crafts—roles previously reserved for higher Varnas—especially during economic hardship. Their humility and dedication made them highly respected by ethical thinkers of the time.

Interestingly, caste distinctions carried over even after religious conversion. In Goa, for instance, many Hindus who converted to Catholicism retained their caste identities. While the Portuguese were primarily focused on increasing Catholic converts and did not initially concern themselves with caste, social pressures led to the continuation of caste-based practices within the Church.

This integration was visibly evident through burrial locations in cemeteries (in the past) and confrarias (confraternities) formed along caste lines within churches. Historically, Catholic priests in Goa often came from Brahmin or Kshatriya backgrounds, mirroring Hindu traditions where only upper-caste males studied religious scriptures or performed rituals.

This historical layering reveals that the caste system was imposed by society on the Church, not the other way around, reflecting the pervasive grip of caste across both religious and secular life in India.