Look no further than to India itself. At major junctions small communities of Goans and Anglo-Indians sprung up. As such the lives of Goans who went to East Africa in search of a better life and better monetary gains were intertwined with the growth of the railway, which became one of the major employers, and gave rise to communities that founded clubs for their after-work recreation and social welfare.

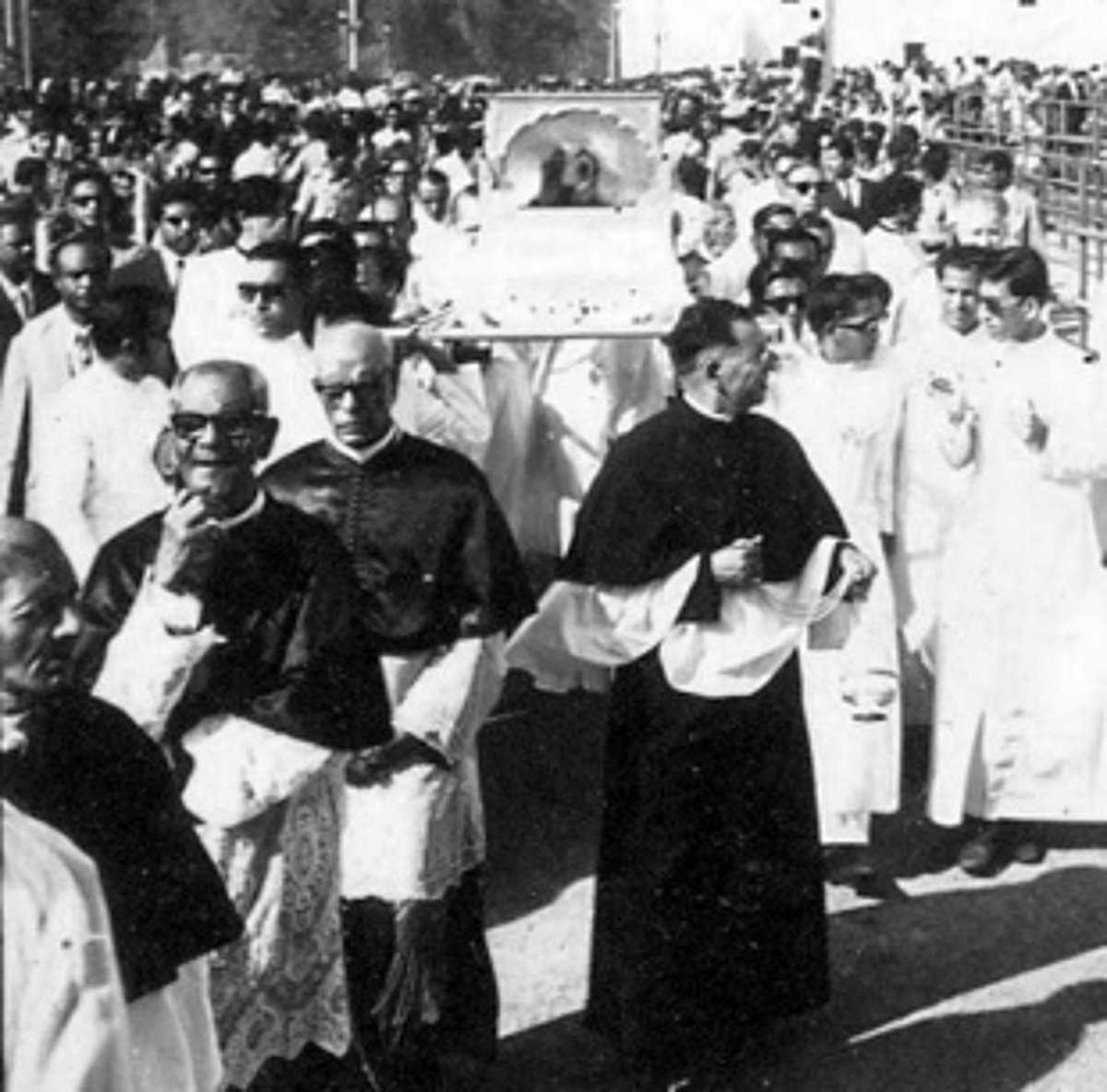

From stepping into the vast and inhospitable land, and with some going into the hinterland to earn their livelihood, Goans conquered virgin territory, making it their base for family and friends. Cities saw pockets of Goans and the activities revolved around church and clubhouse. The community, with all its weakness and faults, progressed. Goans felt cocooned in the arms of a new country, notwithstanding how the natives lived or fared.

As the author Selma Carvalho admits that only a “little of East African Goan history has been documented” and so she, with a grant from the British Heritage Fund, routed through the Goan Association (UK), undertook what came to be known as the British Oral History Project, a series of video and tape recordings with those who had spent most of their lives in the countries that make up East Africa. She captures the sweep of the nations weighing under British colonialisation, and how they at last threw away the shackles of oppression and became free. The Africanisation of these countries ultimately sent Goans, and Indians, packing to new chimes across the globe.

The book traverses many countries, their capitals and major cities, which encompassed Goan communities. It’s a whistle-stop journey into the heartland and the bushland of what was then termed as “Dark Continent.” Goans put roots into the soil and reaped a rich harvest that today forms their treasure-trove of memories which have been nicely collected into the book form, an edited version of the huge load of material obtained from those interviewed and now housed in the British Library, and Bexley Local Studies and Archives Centre.

It’s true that the history of East African Goans wasn’t all that rosy. Those who went there took with them the caste and class prejudices that ruled Goan society in Portuguese Goa. As such, Goans splintered into groups and their caste and class rivalries showed up in the social institutions they set up. The upper-caste Goans frowned upon the lower-caste Goans, for example, the tailors who went with their scissors and measuring tapes to dress and clothe Goans and Britishers. Their lasting legacies remain enshrined in the histories of clubs such as Nairobi Institute, Entebbe Institute, Goan Gynmkhana, etc. Pride and prejudice played havoc with the social life of the Goans that till today the embers of hatred are still burning in their new locales such as Canada, Britain and Australia. East African Goans will never be able to erase this ugly aspect of caste and class warfare from the annals of history.

I was witness to two middle-aged Kenyan Goans arguing over racism in Canada, when one of them said, “We were big racists ourselves and now we talk about the white Canadian’s racial attitudes.” Perhaps, they were looking back at their parents’ or their own behaviour towards the Africans, who were employed as houseboys (totos) or ayahs. The scenario seems akin to lower-class Goans from Goa coming to Bombay in the last century to work in rich households.

The strand that runs through the individual stories of those interviewed has many similar points. Whichever way one may see these Goans, whether they were British loyalists or displayed individualistic qualities or caste/class affinities, as Selma outs it, “self-serving complacency”, Goans created a lasting impact on the East African map.

Encapsulated in this history, is the role of some of the Goans who rose to heights of personal glory and public life. However, these Goans were few compared to the number of Goans settled in these lands. The names of Fritz D’Souza, Pio Gama Pinto, JM Nazareth, Dr Rosanda Ribeiro and Joseph Murumbi Zuzarte, of Goan father and African mother, pop up time and again in the discourse on East African Goans. So are the clubs and the institutes that made up the spine of social amicability as well as social discontent in the mushrooming Goan society. By and large, Goans formed the backbone of the civil administration wherever they went. They formed the second-tier of governance that they became cosy in their adopted lands, much to the chagrin of the bottom-ranked natives.

Very few Goans had sympathy for the African cause and those Goans who were in league with Africans in their struggle for Independence and to find their own feet in their own land were helpless to find no echo to their voice of reason among fellow Goans. One can understand the dilemma facing the bulk of Goans whose succor and well-being lay with the British. Goans felt they were God’s chosen people and kept aloof from the other Indians who outnumbered Goans. Pio paid with his life and it’s surprising to hear today the allegation that his friend Jomo Kenyatta was responsible in his death.

Selma weaves the tales of the lives of people and institutions into a good story. No doubt the story lacks depth, it, however, does open the doors to future research. Since I haven’t read Margret Frenz’s new book, Community, Memory and Migration in a Globalizing World: The Goan Experience c. 1890 – 1980, which tackles similar paths of Goans, these sort of books reinforce what other Goans such as Peter Nazareth, Ladis da Silva, Merwyn Maceil and Braz Menezes, who is working to complete his Matata trilogy, have done to bring into focus the time and temperance of the East African Goan.

The tracks laid down by A Railway runs through should bring onto the research bandwagon those with a keen interest into this aspect of Goan adventure and sojourn in the faraway lands, a dream that many Goans thought would never end. It reminds me of the movie Mississippi Masala, of a Indian man who is forlorn and devastated by what happened to Asians in Uganda, and also reminds me of tales in Moyez Vassanji’s book, Uhuru Street, which captures the joy, the plight and spirit of Asians in Dar-es-Salaam.