When Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru passed away into history almost six decades ago, there were contemplations whether India would hold itself together after him. During the last few years of his life some interviewers perennially put this question to him; Nehru responded with a measure of calmness, patience, impatience, and annoyance. He stated that he and his colleagues had laid the foundation of the Indian state and democracy on very firm grounds; after him, the system would have enough strength to adjust to requisite changes and resist unwarranted tendencies. During the substantial passage of time, subsequently, Indian democracy has survived myriad challenges, if not grown stronger in democratic foundations. Perhaps that is the greatest legacy which Nehru imparted to India.

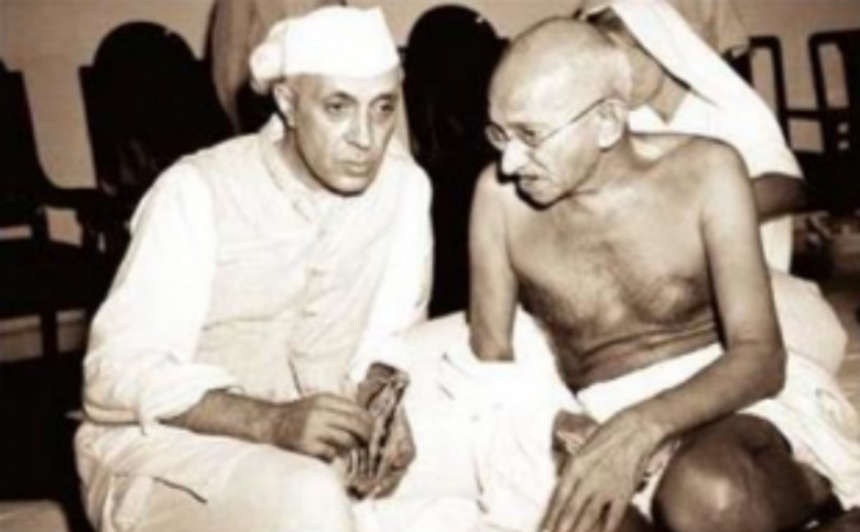

Born on November 14, 1889, Jawaharlal Nehru grew up amid the rising tide of the Indian freedom movement. By the second decade of the previous century, he had immersed himself fully into the hectic activities of India’s freedom struggle from the British colonial yolk. The principal vehicle in this was the Indian National Congress. Before independence in August, 1947, Nehru, under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, worked sedulously towards the stated goal: he undertook exhaustive travels through the Indian countryside, made public speeches in the thousands, attended numerous party meetings, endured several instances of police batons, and spent repeated stretches of time in prison. The joy of freedom and the agony of partition came simultaneously on August 15, 1947. Thereafter, the Mahatma anointed Nehru as India’s Prime Minister. He remained so for 17 years and died in harness on May 27, 1964.

India, at the morrow of independence from British rule, was bereft of any accumulated financial capital, and lacked an abundance of indigenous skilled persons. Nehru took the challenge almost single-handedly to begin administering correctives. An attendant attribute was his being fortunate enough to have some very able and competent political colleagues and officials to assist him. Amid the orgy of political turmoil and communal riots, they worked together to bring about a semblance of peace and order within the country. While political stability was given effect through a collective ethos of political leadership and bureaucratic commitment, the paramount aspect of continuance of people’s representation in the body politic of the country was undertaken through electoral parliamentary democracy.

Would a Presidential democratic system have been better for India? But, that would not have provided an opportunity to represent India’s diversity within a coherent and stable arrangement. In India there are no common unifiers as the earlier Anglo Saxon in the United States, the Great Russian in Russia and the Han in China. Moreover, democracy in the USA and other European countries had been formulated during more permissive periods in history. That was not the luxury which India could afford in those turbulent days of 1947.

Another crucial attribute of Nehru’s legacy was his ability to be able to be receptive to and encourage dissent in politics. Given his tremendous stature and prestige, Nehru could have easily brought about arbitrary governance had he wanted to. But, he diligently saw to it that that was averted at all costs. Even a trace of dictatorship was nipped in the bud.

In economic policymaking and foreign policy formulation, Nehru had proceeded with vision and skill. But, absence of timely modifications sullied the record. In a country, replete with grinding poverty and with a record of near zero economic growth, Nehru’s government wisely chose to make public sector investments a key priority along with welfare policy programmes. A salubrious economic arrangement came into force whereby the government made several investments to propel economic growth in the country. It remained so till Nehru was around. But, thereafter, for the subsequent two decades-and-a-half, public sector economic preference was pushed to bizarre extents. Unnecessary controls choked the economy and discouraged meaningful entrepreneurial activities. Thankfully, the trend has been reversed. But, alongside robust private sector investments, the need for associated requisite welfare measures and social accountability is paramount.

In foreign policy, Nehru’s policy of non-alignment and friendship to all paid India rich dividends. It shielded the country from aligning with any of the two power blocs of the day, enabled it to accrue advantage from wherever it was possible, and ensured a period of prolonged peace, necessary to concentrate on political stability and economic development. However, friendship with China led to a misreading of Chinese intentions of riding roughshod over India at the opportune moment. That was a singular failure of Nehru’s policy. India got jolted on a gloomy autumn of 1962 when the Chinese initiated a conflict of arms with India. Thereafter the country worked and continues to endeavour uninterruptedly to effectively counter Chinese high-handedness.

However, despite several criticisms meted out to him, Nehru was a person of luminous ideas and an outstanding author. He wrote The Discovery of India, Glimpses of World History, and An Autobiography. Each of the three volumes are treasures. They provide excellent insights into Indian history, society, relations with the outside world, and comprehensive perspectives upon other notable civilizations. Reading them would undoubtedly determine a brilliant enrichment of knowledge and strengthening of character.

Today, India is on a far stronger footing in terms of economic stability, political equilibrium, defence capabilities, and foreign policy efficacy. Even then, there seems to be conspicuous lacuna in adhering to the stellar heights of parliamentary propriety, civility in politics, and ethics in public life. These attributes were unremittingly practiced and propagated by Nehru. We could subject ourselves to a critical evaluation of Nehru and his legacy. But it would be better to remember and absorb the positive traits of our first Prime Minister. That would be individually beneficial and collectively enriching for Indian society.

(The author is a columnist with specialisations in International Affairs, the Economy and Indian politics)