VASCO: On December 16, 1971, after an intense battle for 13 days, 93,000 Pakistani soldiers surrendered to India — the world’s largest surrender in terms of number of personnel since World War II and a new country, Bangladesh was created out of Pakistan.

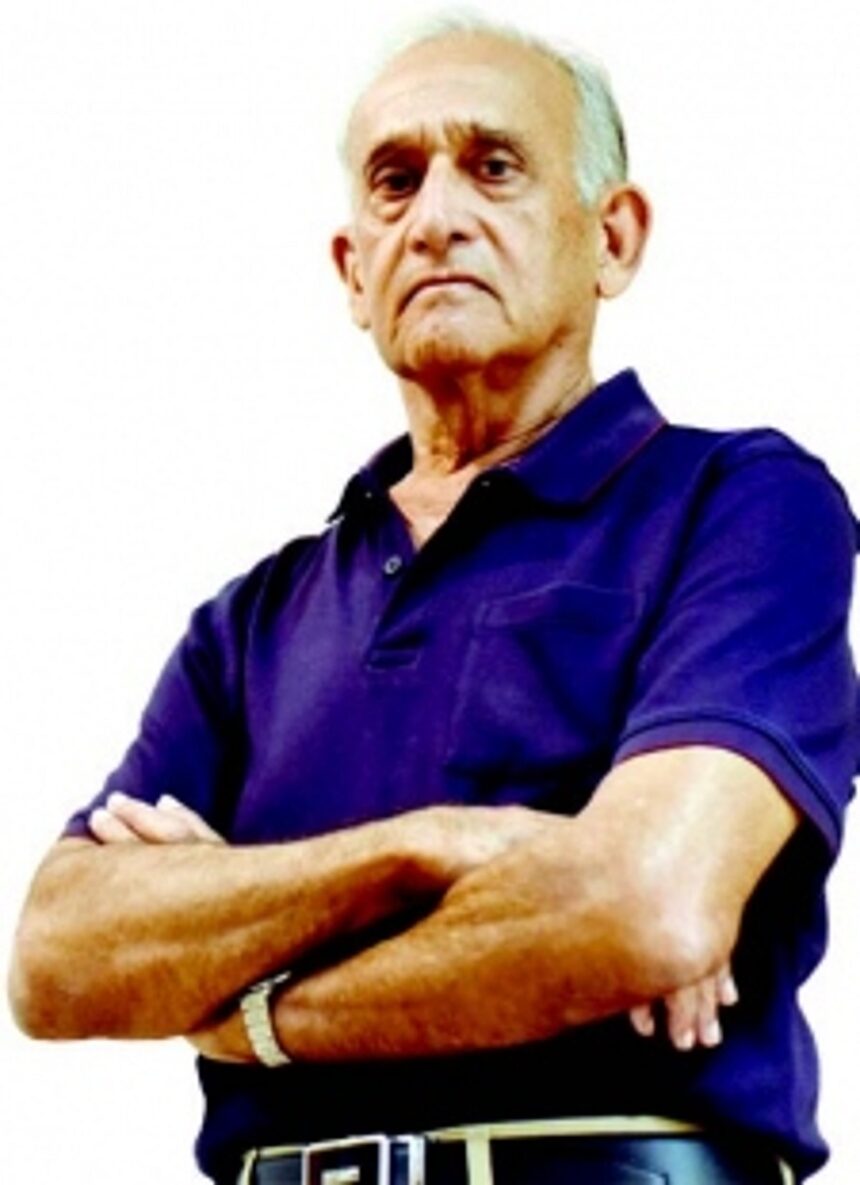

But since then, warfare has undergone a sea change, driven largely by technology. Former Chief of Naval Staff, Admiral (Retd) Arun Prakash, who was on deputation to the Indian Air Force during the 1971 Indo-Pak war and awarded the Vir Chakra for conducting airstrikes deep into enemy territory, says that in the half century that has elapsed since then, India become a nuclear-weapon state.

“We are witnessing the advent of artificial-intelligence, hypersonic weapons, unmanned vehicles, quantum-computing and such technologies. As far as India is concerned, the most important factor that our political leadership and military planners will need to bear in mind, is the risk of a nuclear holocaust, should we engage in a conflict with China and/or Pakistan, both of whom have large nuclear arsenals,” Admiral Arun Prakash says.

When asked about the possibility of deploying low-yield nuclear warheads, designated as ‘tactical nuclear weapons’ in case of full-scale war in future, the former Navy chief says the concept is confined only to the Pakistani military establishment.

“India does not differentiate between ‘tactical’ and ‘strategic’ (or high yield) nuclear weapons. While maintaining a ‘no first use’ posture, India’s consistent, official stand has been that it will consider the use of any nuclear weapon against its cities or forces (anywhere), a nuclear attack on India. As per the 2003 Nuclear Doctrine, India’s response will be ‘massive and designed to inflict unacceptable damage’,” the Admiral says.

“Which means that should an adversary employ a nuclear weapon of any yield against any target in India or against any of its forces, India will detonate a nuclear bomb over an enemy city of its choosing. However, India also reserves the option of a nuclear response in case of a major attack against India, or Indian forces anywhere, with Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMDs) like biological or chemical weapons,” he says.

Despite the infusion of advanced technologies, the essential nature of war does not seem to have changed significantly.

“All these innovations have been employed in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and it can be seen that this 22-month long war has retained all the characteristics of conventional war. There have been occasional threats of nuclear first use by Russia, but this conflict has essentially involved combat between infantry and armoured forces, with occasional employment of air power, and both sides advancing and retreating as of yore. With no end in sight, this war has also confounded predictions that modern wars will be short and sharp,” he says.

Speaking about the key lessons from the 1971 war in today’s context, the senior navy veteran says, “The two salutary lessons that emerged from the 1971 conflict, were: the political leadership must spell out clear-cut aims of the war and indicate the desired end state for war-termination; that there should be the closest coordination in planning and execution of operations between the three services.”

“The same lessons hold good for future conflicts too, except that coordination will no longer be adequate on the modern high-tech battlefield and needs to be urgently replaced by jointness, which would require tri-service formations and unity of command. A third lesson that emerged from the 1972 Shimla Agreement was that, the military must never be excluded from post-war negotiations,” the Admiral says.