PERNEM: The beloved coconut tree plays a significant role in the Goan lifestyle and traditions. Every part of the coconut tree serves a purpose, making Goan coconuts stand apart from those found in other States. However, while coconut trees rarely pose a threat to human life, they often become the first casualties of human development projects.

In ancient times, people lived in houses made of two primary materials: cow dung for the floor and coconut palms woven into walls. These eco-friendly walls offered unparalleled benefits that no modern building material could replicate.

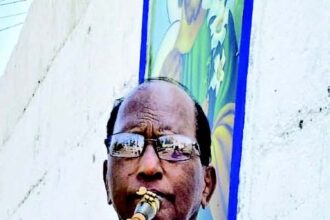

Weaving coconut palms, known as ‘konnam’ in Konkani, was a unique art practiced by men and women alike in ancient times. Surprisingly, many who learned this art didn’t own coconut trees themselves but used it as a source of income. Among the few actual owners of coconut plantations who learned the craft, one stalwart stands out: 85-year-old Raghoba Naik from Hankhane, Ibrampur, in Pernem taluka.

Raghoba Naik is a farmer, and his son and grandson are also engaged in agro-business, owning vast agricultural land along the Maharashtra-Goa border. Despite his age and a life of extensive farming, Raghoba appears healthy and fit. He recalls his decision to learn coconut palm weaving as a means of generating income due to their economic challenges in the backward village.

“I have spent the last 65 years weaving coconut palms and doing masonry work in our village,” Raghoba says, tracing his journey from learning the art from his parents to becoming a sought-after artisan. “Today, I charge just Rs 30 for weaving one full coconut palm. Money is now secondary, I just love my job and the fact that I have earned a lot of goodwill over the years, by weaving these palms for my customers from Goa as well as Dodamarg and neighbouring Maharashtra,” he quips.

Observing Raghoba at work is akin to watching a wizard; his hands move nimbly, weaving four palms in just 30 minutes. “I have achieved mastery over this art. The connection between a coconut palm and me is just too good. The job is set in my hands now,” he proudly declares.

Despite the availability of sophisticated building materials, woven coconut palms remain in demand. Raghoba explains, “Coconut palms are cooling, whether alive on the tree or dried after weaving. They provide shade, have a cooling effect, and are eco-friendly. Eco-friendly resorts, theatre activities, shacks, events, and exhibitions still use woven palms.”

While reflecting on the erosion of Goan traditions, Raghoba urges the preservation of the rich heritage associated with coconut trees. “

We must never forget our roots, never forget that once upon a time, our ancestors lived in houses fully made from ‘konnam’ or woven coconut palms,” he emphasizes.

Throughout his career, Raghoba’s work has been in high demand, bringing satisfaction to his life as he contributes to society. He cherishes two memorable experiences, one involving weaving 500 coconut palms for a natak company within a week, where he pushed hard to complete the order. “The other memory I’d like to share is the time I sacrificed my most valuable asset—a beloved ox—to pay my workers during a house construction project. We completed the construction, but did not get paid and I was unable to keep pestering the owner,” he says. “To my surprise and utter disbelief, the same owner came back after 35 years and paid me as he had realised he had not paid me at all for my labour. On learning that I had paid my workers by selling my ox, he apologised and expressed regret for not paying me on time,” he recalls.

Affectionately called ‘Babal’ in his village, Raghoba’s deep connection with the community is evident. At 85, he continues to receive orders for weaving and vows to pass on his craft to the younger generation to keep the tradition alive.