22626 Bengaluru – Chennai AC Double Decker Express had left Katpadi Junction and it was beginning to turn dark. Suddenly a rumour began to circulate, apparently spread by the snacks vendors that the train may not go to Chennai Central. As it crawled past the areas where the tracks had submerged two weeks earlier our hopes were rising. Finally the train drew into Chennai Central. By then we had got the news that there was no power in several parts of the city and that most of the city was under water.

There were just three autos outside the station; two of them were not willing to move; the third – I felt later he was a little drunk – agreed to drive me to IIT Taramani Gate for Rs. 1,500, six times the normal fare. I had no choice; so we ventured into the abyss of darkness. The passing vehicles – not many – created islands of light in which I could search for familiar landmarks. There were huge puddles of water; some roads were un-navigable. The auto sputtered and stopped, and my heart sank, every moment unsure of whether I had done the right thing by venturing out; but then the driver brought it back to life every time. Just around 10:00 pm we crossed the Adyar River; it was filled to the brim, but not overflowing. As the auto made its way through the dark alleys behind the Kotturpuram MRTS Station, my hopes of reaching home were rising. And finally I reached. Fortunately the power was still on at home.

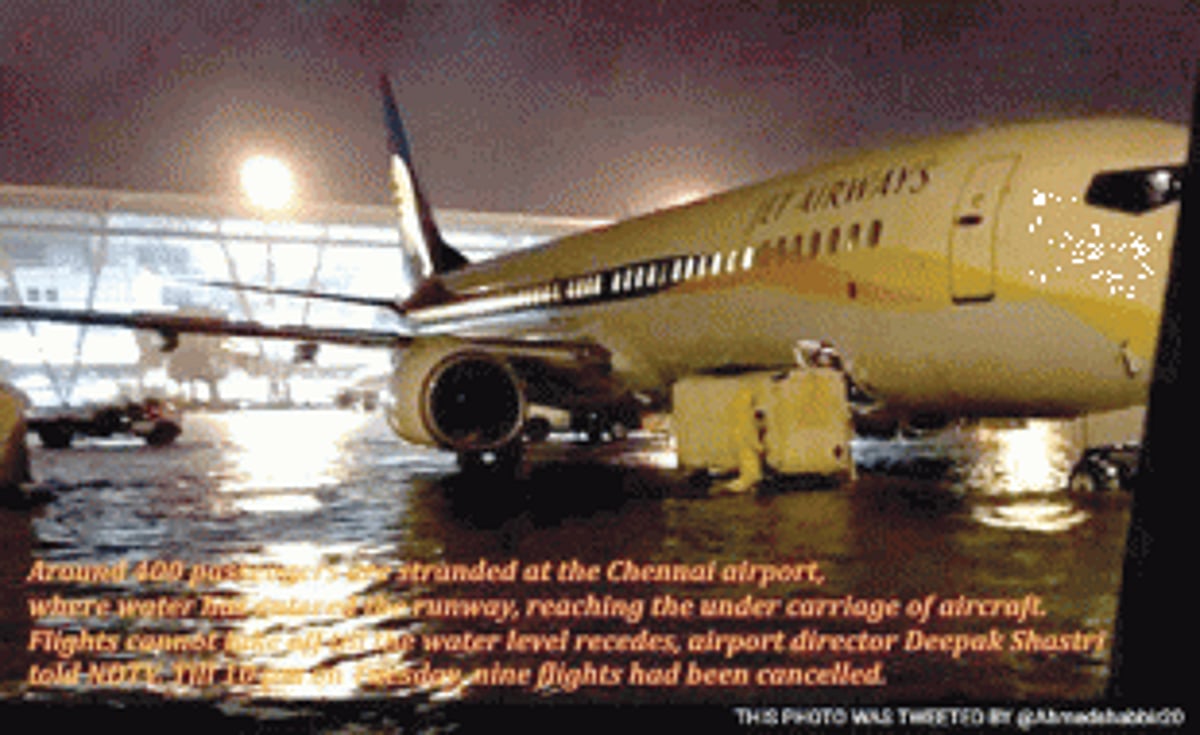

Next morning I learnt that Kotturpuram was under several feet of water. I had had a miraculous escape, just minutes before Adyar broke its banks; at around 10pm the previous night the flood gates of Chembarambakkam Reservoir were opened, pouring over 1,00,000 cusecs of water into the river; Adyar’s carrying capacity is 40,000 cusecs. By 10am we lost power and an hour later all mobile networks were down. Large swathes of the city were under several feet of water; worse still, no one knew what really was happening to Chennai. The airport was flooded; the trains stopped; and buses were stranded; Chennai came to a standstill.

From what I was told at home, it had rained continuously for the whole day on December 1. But all that rain could not explain the deluge. Moreover, the suddenness was mysterious. It is only days later that we came to know what had happened; and that was very important.

In the wake of international weather forecast agencies predicting 500 mm of rain for Chennai on December 1 and 2, PWD officials had advised the PWD secretary and other senior bureaucrats on November 26 to bring down the water level in the Chembarambakkam Reservoir from 22ft to below 18ft so that the lake could absorb heavy inflow four days later. The PWD secretary waited for Chief Secretary’s nod to open the sluice gates. We still do not know for whose permission the Chief Secretary was waiting; it could be for a nod from the Chief Minister. The gates were opened only around 10pm on December 1, after the city was pounded by rain for the whole day and the reservoir threatened to burst. The rest is catastrophic history.

Was that sheer bureaucratic red tape? It could be. But it was much more than that; and that is what is important for us. Seen in the overall context of the situation in Chennai, a decision to release water from the reservoir could be suicidal – be it for the Executive Engineer incharge of the reservoir or for the CM herself. Because, only four months earlier, Chennai was in the grip of an unprecedented drought. The Cholavaram reservoir had gone dry several months earlier; the Poondi reservoir, prime storage point of Krishna water from Andhra Pradesh, had only 54 mcft against its capacity to hold 3,231 mcft; the Krishna water had stopped flowing in a month ago for lack of rains; the combined storage in the reservoirs had touched a dead storage of 988 mcft by mid-July, against capacity of over 11,000 mcft. The scarcity was acute; we would get water for just a few minutes on alternate days; sometimes it would not come at all. There were days we would get up in the morning to find no water for the toilet.

In that ordeal of indecision between the drought and the deluge lay the crux of Chennai’s ecological tragedy – the filling up of its marshlands; both the drought and the deluge were the results of the same. That is the lesson that Goa needs to learn.