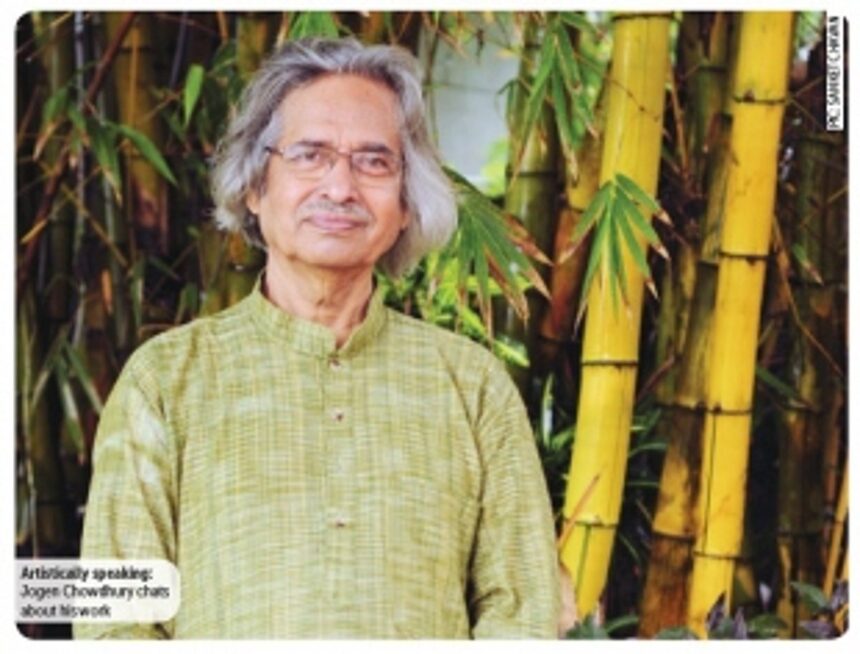

His silver hair is akin to the silver lining

his paintings enjoy today, but Jogen

Chowdhury’s success has much to do with

the trying circumstances and influences

in his early life. For a Bengali who lived

and witnessed the vagaries and crises of

the partition at close quarters, the scars

run too deep. It is one that has inevitable

spilt over into his artistic work. “There

was distressing upheaval on every front

– political, social and cultural. There was

too much suffering. In fact, personally, we

were also deeply affected by the partition.

Our family was from East Bengal, but we

had to shift to Kolkata. The suffering has

not diminished now. I am still unhappy

with the situation in India today,” says

this professor emeritus, Visva Bharati,

Santiniketan, who has been investing

his experiences to bring about an ideal

society that Tagore envisaged.

His iconic black line drawings, which

have been exhibited the world over, has

its genesis in this period. “I recall we had

no electricity when I was in Government

College of Art and Craft. I would work at

night in front of a hurricane lamp. I could use

only black in this light and it has continued

to dominate my work,” reveals Chowdhury

while elaborating that his strong life-study

practice in college, his stint as designer on

the Handloom Board and his innate sense

of rhythm have all been instrumental in

cultivating this further. “It is very easy for me

to draw a single outline in one continuous

stroke without erasing, but I make it more

realistic with tones. I am capable of lots of

toning,” explains this artist who works with

all media.

Studies in Paris and Europe broadened

his perspective, yet Chowdhury has been

influenced by the traditional Indian arts.

“I am very fond of traditional Bengali

art liked the rolled pattachitra paintings

and terracotta relief sculptures. These

influences have been automatically

exposed and infused in my work,” says

Chowdhury whose work combines a blend of traditional imagery with the zeitgeist of

contemporary painting. In 1966, he was awarded

the Prix le France de la Jeune Peinture, in 1986

an award at the Second Biennale of Havana,

Cuba and Kalidas Sanman by the Government of

Madhya Pradesh in 2001.

His expertise was sought as curator at the

Rashtrapati Bhavan for 15 years. The political

atmosphere here once again had an impact on

his paintings. But Chowdhury’s work was to find

its true meaning at Santiniketan where he has

spent 28 years, first as Principal and Head at the

Department of Painting, Kala Bhavana and now

Professor Emeritus, Visva Bharati. “The culture

of Santiniketan gradually influenced me and my

work,” says Chowdhury who admits to being

enriched by the close inter-personal way of

teaching there.

As a newly appointed member of the Rajya

Sabha, he has been making a more fervent case

for art, protesting the reduction in financial

support for arts and pushing for the cause of

cultivating village architecture.