Goans are known for being extremely talented in fields like music

and football among others. Being Goans, we take pride in the rich heritage we

have inherited and carry it gracefully into the generations yet to come.

Intangible heritage of the state like that of its music, song, dance and

stories cannot be preserved as an object in a museum. These are living and

breathing antiquities and if need to be preserved, have to be practiced and

lived.

Music schools that taught to read western music were present in Goa

right from 1545. In 1551, a Jesuit missionary, Gaspar Barzeu (associate of

Saint Francis Xavier), introduced choir masters, organ accompanied chants and

sung mass. Goan song is part of the tradition of song in Konkani, which is the

language of Goa. The theme for Goan song is life, expressed in three of its

sides. The ultimate meaning of life (includes religious pieces), the crucial

moments of life (birth, death and middle age) and the festive occasions of

life. The various types are popular art songs (songs without a set theme),

religious songs (Fugrhi), theatrical songs (Tiatr songs, zagor songs),

childhood songs (Palnnam), caste based songs (Dhalo),

occupational songs (work songs sung by toddy tappers), random folk songs

(miscellaneous folk songs celebrating random moments), death songs (Dirges),

marriage songs (Ovi, Shobhane), and dance songs like ‘Deknni’,

including the Mando. The Mando is a form of 19th century Goan song which fits

into a class of songs called ‘Dance songs’.

Until the middle of

the 19th Century, the ‘Ovi’ (Vovi), a wedding song (banned in

1736 by the Portuguese Inquisition, but in use up to the mid-20th Century), was

Goa’s most well-known form of musical expression. It is from this ‘Ovi’, that

the Mando could have had its origin. Like these ‘Ovio’, the earlier

Mando comprised of stanzas containing four lines while the Mando of the later

years was probably influenced by the Portuguese Fado where the chorus

was added to the traditional four lined stanza. The Fado was surely relished by

Mando composers being quite similar to each other in many ways. As presumed,

the Fado is sad but the Mando is sad and intense. The Mando, as mentioned

earlier is a dance song which allows us to assume that it was created after the

introduction of ballroom dancing in Goa somewhere in the 1830s.

Frederico de Melo

(1804-1888) one of the earliest known composers of the Mando from Raia, said

that the Mando was still a single couple dance in the 1840s. The Mando may be

recognized as India’s noble ballroom dance fit for royalty and is an

anachronistic fusion of 18th Century dances like Minuet and the Contredanse

which is perhaps the last dance to have been created in conformity with that

perfection. The Mando carried and conveyed emotions of love. It also played a significant

role in documenting contemporary events especially of political and social

nature.

It was during the

period spanning from around 1840 to 1950, that the Mando was born and

flourished. It originated mainly in the South of Goa, among Kshatriya (Chardo)

and Brahmin Catholic families from villages of Curtorim, Margão, Loutolim and

Raia. We do not really know the origins of the word ‘Mando’. However, there are

high chances of the word being derived from the ‘Maand’ (a gathering

place/a temple stage) or from ‘mandavoll’ (arrangement of dancers and

singers observed at the time of performing the Mando).

The Mando follows

four basic themes: a) yearning for union (utrike); the union attained (ekvott);

lament out of despair for union (villap) and finally a narrative of

events that may be domestic, political or local (fobro). Musical

accompaniments traditionally used while singing the Mando would have been a

violin, a guitar and rarely a piano. Interestingly today, the Mando is

incomplete without the ‘Gumott’ (a percussion instrument comprising of a

terracotta pot with two openings on opposite sides. The wider opening being

covered with monitor lizard skin). It is important to take note that the Mando

was performed by the elite while the ‘Gumott’ is a tribal percussion

instrument used by the Gawda community.

Now the question is,

how did the ‘Gumott’ become such an integral part of today’s Mando?

Probably, it could be that the family members of the ‘Gawda’ community who

assisted with the daily chores at their landlord’s house, would have witnessed

the Mando being sung and danced in their ballroom halls. Hence, somewhere down

the years they may have contributed invaluably to the Mando by introducing the ‘Gumott’

to the whole musical setup.

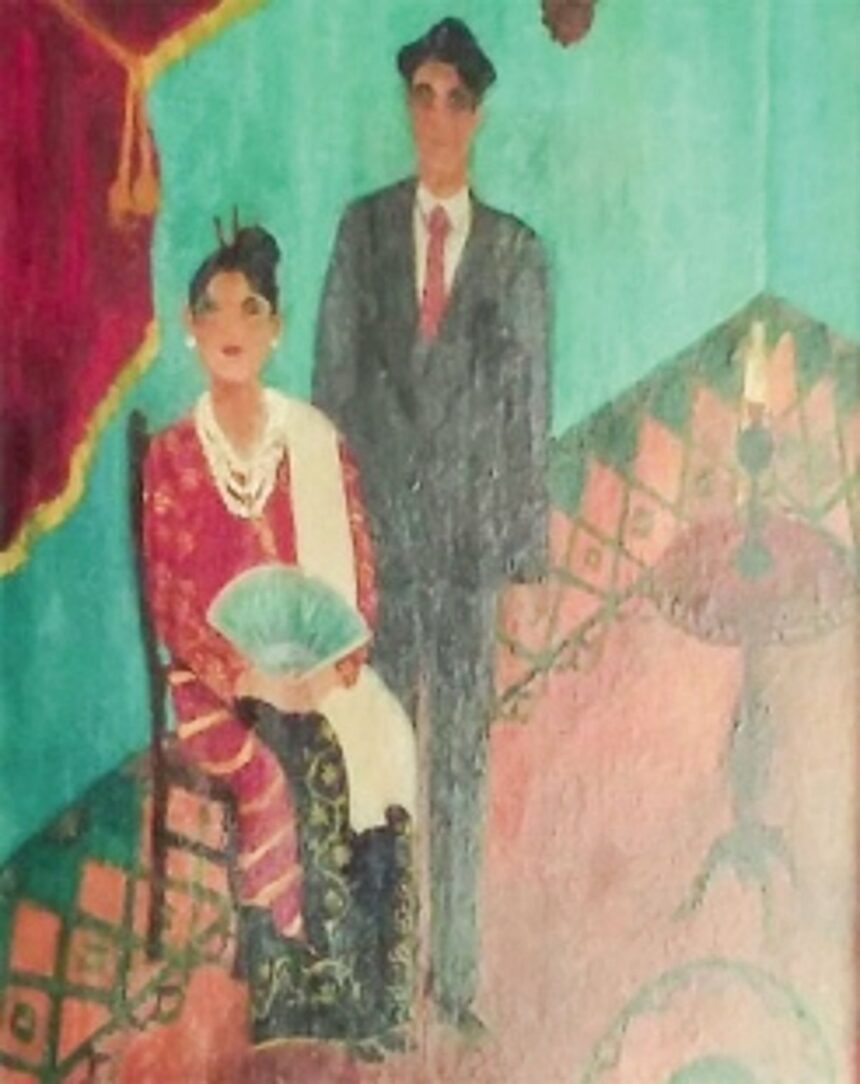

In an attempt to

understand about the outfits worn by the men and women who participated in the

singing and dancing of the Mando, we are able to understand that the men of the

19th Century adopted a dress, then in vogue in Europe, by reluctantly giving up

wearing their ‘Cabaia’ and ‘Kaxtti’. The newly adopted outfit

would have comprised of a suit with a tailed or untailed coat and a collar bow.

The costume for women was the ‘Torhop-baz’ (Pano baju). It

consisted of three pieces: the ‘Torhop’ (a wraparound skirt), the baz or

blouse, a shawl (tuvalo) and flat gold/silver thread embroidered velvet

shoes (Chinelo). The ‘Torhop’ was like a stylized version of the

traditional Indian women’s loin cloth, roughly 90 by 150cm, with a horizontal

and a vertical border.

There are two types

of ‘Torhops’, one for festivities or ceremonies and the other for

mourning. The mourning ‘Torhop’ was black and white adorned with black

or red borders (a red border indicated that the deceased was a relative or a

parent while a black border meant that the deceased was the husband). This

black ‘Torhop’ was worn until the first death anniversary, after which

widows wore black ‘Torhops’ with a blue border for the remainder of

their lives. Married women wore red bordered ‘Torhops’ but without any

black in their whole attire. These were generally made of velvet or silk (red,

blue or green) and embroidered using gold thread (silver was rarely used). A

white, blue or yellowish shawl was worn along the left shoulder. Pieces of

jewelries used by women included ‘Pedro Vitorine/Pedro Verde’ (malachite

lantern earrings), Cordão (gold beaded necklace with multiple rolls), Chamfim

(floral hair adornments made of gold), Bangles, ‘Pedra Verde’ necklace

(colar), etc.

When Mando was being

performed, in some parts across Goa, it was customary for a man to hand a woman

a card inscribed with the name of the dance he wished her to partner. If she

agreed, she would join the file of women along one side of the ballroom, while

the man would join the file of men along the opposite side. In complete

silence, the strains of the Mando sung solemnly would impel the files into

motion with movements of advance towards the right, front, left and finally a

three-quarter view in a slow graceful manner. When almost facing each other in

the middle of the ballroom, the couple would split and retreat back to their

starting points with advance followed by recess. Another advance was soon seen

with the men and women gliding toward each other with the whole pattern of

movement rounding off into a crossing and interchange of places.

The men tried every

gesture while he danced. Flicking his handkerchief, soldier like salutes,

placement of one’s arms in a cross folded manner and sometimes even strange hat

adjustments were made. At the end of the dance, the woman would find herself

unable to dance any further. The man wiping the sweat off his forehead would

then victoriously take her back to her seat.

Fr Mansueto Fernandes

(a musician), the assistant parish priest of the Igreja de Regina Martyrum,

Assolna, says that hardly any young people appreciate the Mando. “Children have

not been introduced to this form of music and this lack of exposure is one of

the primary reasons for them being careless towards the Mando,” he says. Fr

Mansueto is of the opinion that the future of the Mando is bleak with extremely

few youngsters showing an inclination towards learning to sing it.

Ivo Gonçalves, a

Mando enthusiast from Moira says, “The younger generation, somehow lack the

skill of putting in emotion and instilling life and meaning into the lyrics

they are introduced to,” while he seconds the opinion of Fr Mansueto on the

uncertainty of the future of Mando.

Margarida Távora e

Costa from Raia, South Goa, India, member of ‘GAVANA’ a troop of singers,

musicians and dancers expresses her concern towards protecting the art of

singing the Mando, for posterity. “In the olden days, it was mandatory for the

bride to sing the Mando and for couples to dance to it’, she says, while she

also mentions that Mando festivals of the 1960s/70s were classy with great

groups participating. Ranchi Viega Coutinho from Margão being one of the

winners of that era. Over time the number of groups performing Mando along with

the quality and class in the performances has reduced drastically, she exclaims.

Margarida

feels that the Mando is a dying art form but however if likeminded people come

together with the sole intention of reviving and preserving it, the same can be

accomplished. She mentions that in her younger days, together with her group,

she would sing with passion and for free but now this is not the case anymore.

Margarida also expresses her kind appreciation towards some of the well-known

groups of the day which do a commendable job of keeping the Mando alive. Now is

the time to revive this truly Goan 19th Century form of singing and carry it

ahead into the generations yet to come.