68years ago, in his electrifying public debut with the essay

Nirvana of a Maggot – it was published by Stephen Spender in Encounter –

Francis Newton Souza described his feelings after a summer in Saligao: “I

patted the earth and thanked heaven that there was at least a small plot of

land left on this planet which has not been poisoned by our ghastly

civilization, if it can be called that, with its mechanised fangs that were

simply and surely sucking the life out of us.”

Obviously, that lull did not last, but

there’s something else Souza wrote in 1955 that remains entirely apt, which is

his acute summary of artistic motivations for painters like him with something

to communicate: “I want to say something, to make just a sound, even a guttural

sound or a grunt, an onomatopoeic sound emitted with a clearance of the throat.

What I’d want to do is to suspend my vocal ‘cords’ on the nib of my pen like a

mouthful of food at the end of a fork; to throw my voice like a

ventriloquist’s, but over a page; to emit sounds with gummed backs like postage

stamps which stick firmly on paper; to make the split point of my pen the

sensitive needing of a seismograph, as I can easily do when I draw.”

Those lines have come to my mind many

times in viewing and experiencing the spontaneous, and often deeply moving

responses by many artists and writers of Goa to the shocking betrayal of

“Mother Mhadei” by the state government, which has meekly acquiesced to

destroying our ancient riparian ecology by diverting billions of cubic feet of

water, in yet another “match-fixing” for the BJP’s selfish political gains. It

is an inherently desperate situation, as the state runs roughshod over public

sentiment, and citizens left effectively voiceless.

It was in that atmosphere of collective

helplessness that I first encountered Miriam Koshy’s heartfelt मãi : Mhadei’che Rakhondar in the

unexpectedly thought-provoking Poetry in Colour group exhibition last month at

the gorgeous Instituto Camões premises on the Mandovi waterfront.

In her accompanying note, the artist

explains that “my art dwells on the interconnectedness of all beings in nature,

human and more than human. It is an excavation and examination of layers, a

deeper understanding of self and one’s environment. It is through the process

that reconciliation, catharsis, and a spiritual, psychological, energetic shift

happens. I strongly believe in the power of public art, taking art from less

accessible spaces like galleries and museums with the intention of holding

space to process ecological grief and evoke awareness and meaningful responses

to climate change and environmental issues.”

Powerful sentiments, but can mere art make any difference when

opposed by armies of bulldozers and the unbridled might of the state? Here in

Goa, the answer is yes, and we already have the example of #MyMollem, the

brilliantly innovative campaign that has – so far quite successfully – fought

the most pernicious oligarchic interests and their destructive plans to carve

through the Bhagwan Mahaveer Wildlife Sanctuary and Mollem National Park with

three patently unnecessary giant projects.

This highly inspirational millennial-led movement’s leader, Dr

Nandini Velho once explained to me that “the business and politics of nature

conservation should no longer just be in courts, and conducted by environmental

groups and scientists. These art-science or nature-culture dichotomies belong

to a different era. Art creates a bridge that is understandable, relatable and has

longer staying power. It conveys stillness and sense of place. The art for

forests under threat including Mollem, Dehing-Patkai in Assam, Etalin in

Arunachal Pradesh, and Vedanthangal in Tamil Nadu are some of the best forms of

activism I have seen, and it makes me super hopeful.”

It is in this context that Koshy’s fragile, lovely guardian

spirits – which is what “rakhondar” means in Konkani – are best understood, as

another iteration of her complex environmental installations that first gained

national recognition with Mangrave: (En)circling the Loss, an anguished group

artwork – attribution is to “the Earthivist Collective” – in the ruined khazan

lands of Merces, of which an unforgettable drone image later appeared on the

cover of Outlook magazine in June 2022.

Mangrave’s spine was a spiral installation of prayer flags made

of gauze, that visitors had to wade out to visit in an apocalyptic dead zone of

ruined mangroves. Koshy says that site, and the myriad associated activities

that brought hundreds of people into the mangroves, were “an invitation to

pause, witness, experience, engage and add to the much-needed collective

healing in the face of the constant onslaught of ecological grief we face with

each passing day.”

These is such a lovely aspiration, and I was struck by how

substantially it has been achieved in my second viewing of Koshy’s rakhondars,

in the soft evening light (see picture) at the lovely Fundação Oriente premises

in Fontainhas, during this week’s World Heritage Day commemorations in collaboration

with the Goa Heritage Action Group (of which both Koshy and I are members).

There

was lots of emotion in the audience, as we listened to an urgent presentation

by the senior engineer Sandeep Nadkarni, and poems by Salil Chaturvedi (see

attached box) and Rochelle D’Silva (accompanied by Ben Ferrao). Meanwhile, in

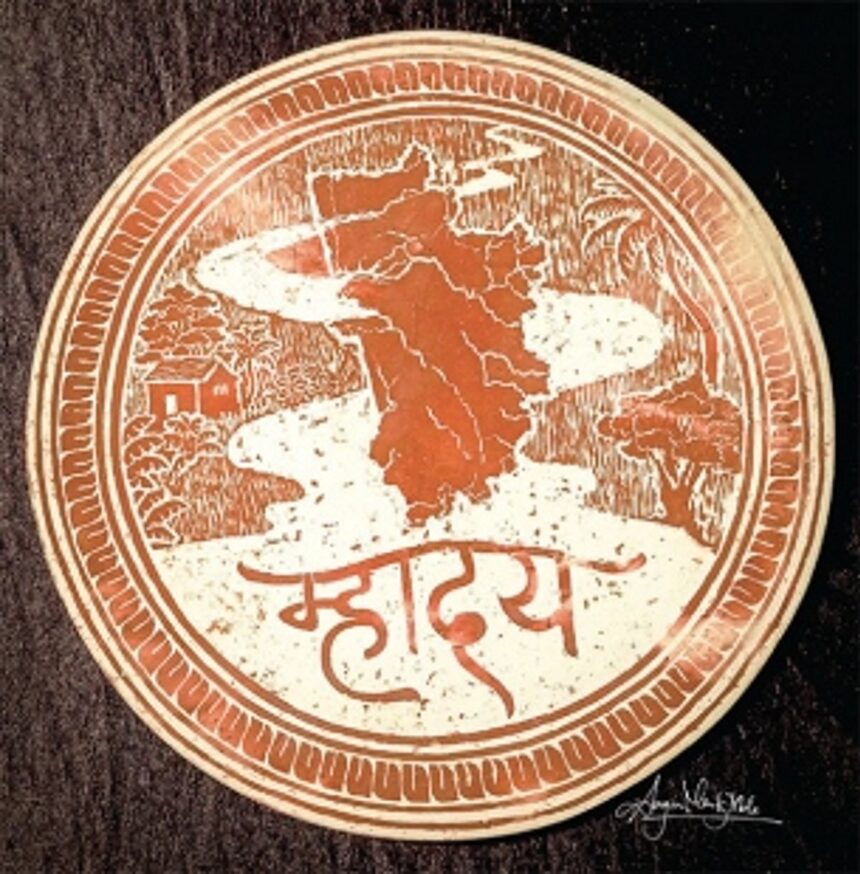

one corner of the room, Sagar Naik Mule worked on the lovely contemporary Kaavi

artwork that you also see alongside this column, and when I asked him to

explain what was on his mind, he told me this: “Our Goa is full of greenery and

it depends on the Mhadei as well as other rivers, due to which we are having a

good life and healthy atmosphere. So I have shown the water flow of our most

important river, and in the centre there is our land, which is totally reliant

on it. Sadly, because of dirty politics and their corrupt minds, our leaders

forget the importance of it, and they are playing dirty games which will harm

nature. This is my prayer for better wisdom to prevail.”