What’s not to love about Panjim, the capital city of Goa? However, every aspect that one sees today in the main city centre were planned centuries ago and are still standing. For the first time, a two-day national conference of Urban Design and Resilience of the Indian city organised by the Institute of Urban Design will be held in Goa on September 29 and 30. Some of the noted architects who will be present for the conference include KT Ravindran, professor and head of Urban Design at the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi and Professor Neelkanth Chaya, who retired as the dean of School of Architecture at CEPT University, Ahmedabad.

The national conference in Urban design were invited by a special request by the Goa College of Architecture to bring attention to the students of masters of architecture in urban design, which recently commenced at the college. However, those interested will have to register for the interesting sessions about planning, migration, cities and climate change.

Dr Vishvesh Kandolkar, Vice principal of Goa College of Architecture will present a session today, September 29, on ‘Panjim as a resilient city through history’. “My talk will focus on the Resilience of Panjim as part of Portuguese city. The history of Panjim is also the history of the downfall of Old Goa. Panjim has been the capital of Goa since 1843 and the material from Old Goa was reused or recycled in Panjim. The Afonso de Albuquerque monument was at Azad Maidan earlier. There are 12 Doric columns there which are aligned today. Now, this monument, which was meant for a significant secular figure, but those columns are brought all the way from St Domingo’s Church in Old Goa. This is the recycling of materials, and those materials still exists. While it’s about Panjim’s history, it also Old Goa’s history and very few people see that kind of history connection,” explains Dr Vishvesh, who also did an exercise about the sea water rise and its impact in Panjim with his students.

He informs that the entrance to Adil Shah Palace which has huge stones, which are also seen at the entrance to Accounts department, the department which was earlier Vasco da Gama building, they actually came from Old Goa. But these granite stones first came from Bassein (Vasai) near Bombay. They were bought from Bassein in order to decorate Old Goa and then they were brought to Panjim to decorate the new city. The stones were brought from nearly 600 kilometres because that hard grey stones were available only in Bombay, as in Goa, we find laterite stones. “When it comes to the history of Panjim, one has to also think about the connections via Old Goa to all the way to Bassein, which is the resilient history of materials,” he says.

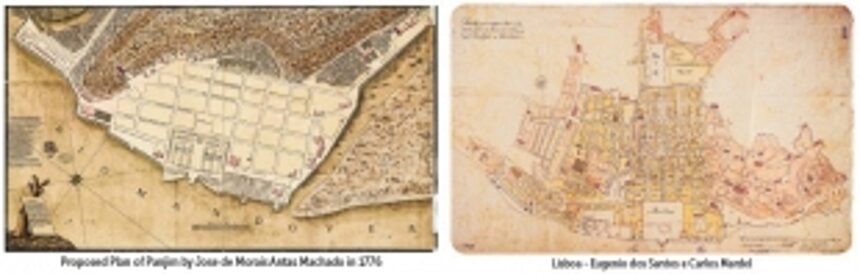

How was Panjim planned on a grid system? In 1755, there was an earthquake followed by fire followed by tsunami in Lisbon. Subsequently, Marquis of Pombal was selected as the minister to revive Lisbon. He revived Lisbon by redrawing the map of Lisbon in a grid fashion. “He was a secular speaker who was trying to revive Portugal’s Lisbon and that plan was first brought to Old Goa in 1774 and the same grid plan was drawn for Panjim in 1776. Panjim, Old Goa and Lisbon were drawn on the same lines of planning. The main part of the city we see today, the grid layout is the legacy of Marquis of Pombal. This history of this urban form which requires us to connect back to our past which links Marquis of Pombal, to Lisbon, Old Goa and Panjim, apart from the materials transfer,” adds Dr Vishvesh.

Dr Vishvesh wants to connect to three parts, recovering history of its urban form, which is inspired by Marquis of Pombal And recovering its history where the material itself was transferred from Old Goa to Panjim, which includes the Bell of St Augustine’s Church in Old Goa, which has gone to Our Lady of Immaculate Conception Church, Panjim in 1871 and the columns of Afonso de Albuquerque which comes from St Domingo’s church.

“Panjim is unique, and for any modern development, which ignores its history, is also ignoring the resilience. Despite our ignorance, many of these artefacts continue to survive. So it’s resilient in a way that those evidences of the past are still there, and they are refusing to be erased. I want to think of Panjim as a city of resilience through history, that all these layers makes it an interesting example. Many people have done this modelling of Panjim for climate change too,” concludes Dr Vishvesh.