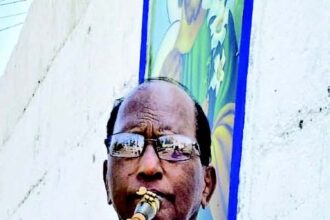

ALDONA: Goa once boasted of specialised professionals in each taluka—renowned masons in Pernem, skilled carpenters and painters in Bardez, and adept bakers and pastry chefs in Salcete. While Pernem’s masons persist, Bardez’s craftsmen have faded away, and many Salcete bakers have migrated to Bardez. Amid these changes, 59-year-old Tome Reginald Fernandes stands out as a son of the soil, keeping his family’s baking profession alive in Corjuem, Aldona.

Tome proudly recounts his family’s journey, highlighting how his ancestors migrated from Salcete to Bardez around the time of Goa’s Liberation. His father, setting up shop in the sleepy village of Moira and later in Corjuem around 1963, established the family bakery. Tome vividly describes the early life of a baker, walking with a bamboo basket filled with bread covered by a large leaf plate, perched on his head. He recalls his father covering a large area, walking with the bamboo basket, and fondly reminisces that he later bought his son a cycle, making him a rare baker who continues to distribute bread on a cycle.

“If I run the bakery today, it’s all because of my father. My happiness lies in keeping his business alive and serving his loyal customers,” states Tome. He recalls a childhood of balancing work and school, tasked with the daily duty of waking up early to distribute bread before attending school. Despite the challenges, Tome cherishes the memories of those days, including the flavourful influence of coconut toddy that was used to ferment the dough. “With fewer toddy tappers operating and hight cost of toddy, all commercial bakers have been forced to use yeast,” he rues. “Flour would also be brought on a bullock cart from Mapusa, unloaded onto a canoe and brought across the river. Another cart on the Corjuem side would then ferry the flour to our house,” he recalls fondly. His father served a large area – Aldona, most of Corjuem and even parts of Mayem. Weekends were the most exciting time as Tome and his brothers would cycle to the bustling Mapusa market on Fridays and Aldona markets on Saturdays, to sell their bread.

Expressing concern for the decline of genuine Goan bakers, Tome points to issues like labour problems, the entry of non-Goans disrupting fair pricing, lack of government support, and scarcity of firewood. He urges the government to develop policies supporting traditional Goan professionals, proposing a system to provide wood

sustainably from the roadside trees that are trimmed and cut all over the State. “Earlier, bread would only be baked once a day, and the bakery

operated solely at night. Increased demand and stiff competition now require baking twice a day, leaving bakers with little personal

time, hardly any sleep and no life,” Tome says wistfully, adding that he churns out 2,000 pieces of bread each day including kator, kankon, poie and pao.

Tome, now working with his wife after losing previous workers, acknowledges the decline of genuine Goan bakers. He has instructed his children to stand on their own feet, continuing the family business only if necessary. Despite stiff competition from migrant bakers, most orders from

Aldona and Corjuem still go to Tome.

He expresses gratitude for

the love received from customers, emphasising the need for fair

pricing to preserve the Goan tradition.

Tome has also been doing fish farming for the last 20 years. As he reflects on the future of Goan poder (baker), Tome believes that unless the Goan youth are enticed by the government, the tradition will continue slipping away from their hands.