ERWIN FONSECA

ANJUNA: Goa’s vibrant culture is deeply rooted in its traditional art forms. While modern entertainment gadgets dominate today’s lifestyle, earlier generations sought solace in local performances, marking the birth of art forms like Konkani plays and tiatros. A lesser-known but equally significant tradition in North Goa is the zagor. Unique to villages like Anjuna, Siolim, and Calangute,

this centuries-old art form is a beloved tradition being kept alive despite migration of many in these villages.

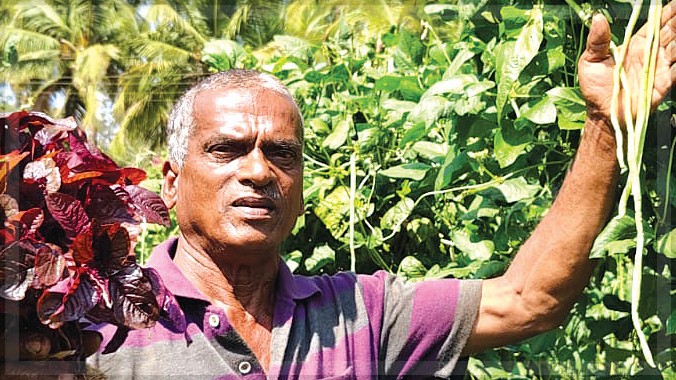

Among the foremost champions of the Anjuna zagor is Assunção Piedade Fernandes, fondly known as ‘Pidulo’ uncle.” Now in his late seventies, he is a treasure trove of knowledge about the art form and its evolution. Despite physical challenges—he is handicapped in one leg—Pidulo uncle continues to play a pivotal role in the zagor. He recalls participating in it immediately after Goa’s liberation, when he was in his early teens, and insists the tradition existed long before, with his ancestors performing with great zeal.

Reflecting on the journey of zagor, Pidulo uncle explains that the venue used to alternate between Grande Pedem and Pequeno Pedem in Anjuna until the latter became its permanent home. “We initially called it ‘Abelachem Sopon’ (Abel’s Dream), named after Abel D’Souza, who suggested moving it here,” he recalls. Preparations for the event start a month in advance, involving local villagers who are determined to keep the tradition alive.

The zagor begins on the eve of the village church feast with a litany (ladainha) at the chapel cross in Pequeno Pedem, followed by a procession and an overnight stage performance. During earlier times, girls were prohibited from acting, so boys would don female attire. “There was always one lady responsible for dressing up the boys. The transformation was perfect, with people cheering them on,” he says with a nostalgic smile.

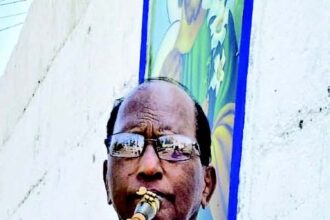

Music has been a key element of zagor, with traditional instruments like the ghumot, maddein, and kasaim setting the rhythm. “The boys playing these instruments are often fishermen who take a day off to participate. It’s a village feast—a celebration for everyone,” explains Pidulo uncle.

Over the years, professional artistes and women have joined the performances, adding a new dimension to the zagor, but the emphasis on local talent remains strong. Pidulo uncle notes that humour and original compositions continue to be crowd favourites, although they avoid potentially offensive topics.

“Support from parish priests has been instrumental. They motivate us, attend as chief guests, and enjoy our performances,” he shares. The zagor at Anjuna also enjoys strong ties with Calangute, where artistes and writers historically contributed to its success.

For Pidulo uncle, zagor is more than just entertainment; it’s a unifying force for the community, bridging divides of caste, creed, and religion. “It’s satisfying to see this tradition thriving. It’s all about local talent, unity, and keeping our culture alive,” he affirms with pride. As long as the villagers’ dedication endures, this timeless art form will continue to resonate with generations to come.