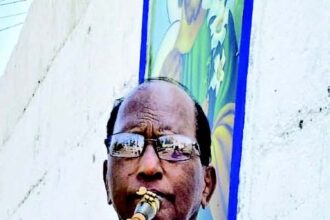

BENAULIM: Upon entering Anthony Furtado’s wood shop, where the floors are carpeted with wood shavings and the symphony of machines drilling fills the air, one steps into a realm of craftsmanship that spans generations. Located in Benaulim, this small wood workshop, established before 1947, is a testament to generations of skill, and dedication. Antonio Mariano Furtado, 56, proudly carries forward a legacy initiated by his grandfather Menino Furtado, persisting for over seven decades. Anthony, the last carpenter in his family, has crafted a narrative steeped in tradition and mastery.

Amidst the whirring of the workshop’s machinery and the aromatic scent of freshly cut wood, Anthony’s journey began at the tender age of 10, working alongside his father. On returning from school every afternoon, he would observe his father’s adept hands shaping wood, absorbing fundamental techniques, and assisting with minor tasks. Meanwhile, his grandfather toiled diligently, sculpting altars, and crafting wooden furniture for churches and homes.

Reflecting on his father’s sentimental attachment to furniture pieces, Anthony remarks, “As carpenters, we furnish other people’s houses; nothing we make is for us.” Soon after, Anthony’s father ventured to the Gulf for work, a 12-year-period which marked a departure from the routine. In the absence of his father, Anthony, alongside his brother and mother, assumed the mantle of the workshop’s daily operations. Even his mother turned woodworker and did not shy away from the strenuous tasks. Starting early in the morning, the family established a daily 3 pm tea-break ritual, a brief pause to watch a cherished daily soap, before seamlessly resuming their labour until closing time.

“We have never had a day where things are not busy; we are always overloaded with customers,” he asserts.

Adapting to the contemporary era, Anthony navigates the intersection of tradition and technology. Googling new-age designs and customising them for specific spaces, he underscores the unmatched quality and fit derived from personalised craftsmanship. However, he laments, “It saddens me to say I’m the last carpenter in the family. I have three daughters, and while my eldest managed the shop during my absence, she is now married.”

Bemoaning the scarcity of local Goan apprentices interested in carpentry, Anthony reveals his struggle to find successors. In a world enticed by fast money and foreign prospects, the prospect of carrying on a legacy requires sacrifice and dedication, he explains. “No partying, no nightlife, just work hard, and then you can relax for a lifetime,” he advises. Recalling his learning years under his father’s guidance, Anthony reminisces, “My dad never scolded us or forced us to learn anything. Interest was the key factor.” The manual labour of yesteryears, as he describes it, reveals the challenges of an era when even a simple saw required synchronised efforts from two individuals. With a chuckle, he recounts his father’s ingenious use of a diagonal saw to deter mischief.

Anthony’s work extends beyond the confines of his workshop, reaching into homes and churches. Renowned in his community, his recent endeavour involved crafting an altar for the Chandor church. Living a simple life with his three daughters, Anthony confronts the hurdles of health and recounts an incident 15 years ago when a wood cutting machine claimed two of his fingers. Undeterred, he persists in his craft.

Now 56, Anthony remains committed to adorning homes with his craftsmanship. He advocates for foundational learning, highlighting the importance of institutes like ITI in teaching correct techniques.

As he continues his journey, Anthony embodies not just a carpenter, but a custodian of tradition, navigating the delicate balance between heritage and the demands of the present.