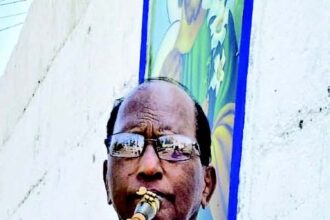

Joseph Fernandes

ALDONA: In the bygone days, bunches of little, pinkish-purple onions hanging from an overhead beam in the kitchen was a common sight at every Goan home. The bunches were especially large during the summer months of April and May when each family began making ‘purument’ (provision) for adequate food items to last through the monsoon. The onions, which were needed for just about any preparation, were known never to spoil and were used sparingly until the end of the rains.

Cut to the present day, however, and the demand for these locally grown bulbs continues to fall as cheaper onions from other states flood the markets despite having a much lower shelf life. Savio D’Souza, a farmer from Ranoi in Aldona, rues that this is unfortunate because although they are costlier than regular onions, the local variety is not only packed with flavour but also has great medicinal value. He says they are famously crushed and fermented with sugar overnight and the syrup produced is consumed as a treatment for coughs the next morning.

“Besides this, many people would fry the onion and massage it on their bodies for instant pain relief. The best part is that they are free of pesticides,” D’Souza says. “Only the people who appreciate the value of locally-grown onions buy them. Some even book them in advance.”

Having learnt the process of cultivating local onions from his mother, D’Souza is keen on keeping it alive lest the power-packed, indigenous bulb die an unceremonious death. “Here’s how we do it: We first burn the fields to clear the stubble and weeds and dig the ground and make rows. Then we mix in natural manure, such as cow dung, sow the seeds and continue watering the soil. The area is covered with hay until the seeds germinate. The saplings are subsequently removed and replanted in another area,” he says.

The tricky part is irrigating onion plants. “Great care has to be taken,” D’Souza warns. “As the bulbs themselves grow, less water is given. They are then uprooted and spread out in the fields for drying after which they are tied into bunches for preservation and sale.

The process might look like a cakewalk for the humble farmer, but it is far from it. Apart from the back-breaking labour involved in growing the onions, inclement weather – such as unseasonal rain – sometimes ruins the crop. Porcupines foraging for onions and ruining the field as a result is also common, D’Souza says. “But I am not one to give up easily. I persevere. Today, I am proud that I cultivate a large volume of Goan onions on my own and have sufficient stocks for personal consumption,” he says.