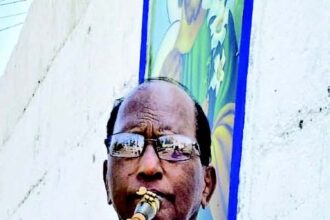

ALDONA: Pravin Manohar Shet, a resident of Corjuem, belongs to a family with a rich history of fishing that has been passed down through generations. Alongside his work as a mason, Pravin continues the legacy of ‘Aar’ fishing, a unique and labour-intensive method perfected by his aa and ancestors.

The Shet family has been engaged in this craft for over a century, preserving a way of life that might not be carried on by future generations. ‘Aar’ fishiang, which involves using wooden poles called ‘maddi’, made of bamboo or areca, set in the middle of the river, requires precise timing and effort, often necessitating late-night vigilance to monitor water tides. “I’ve spent over 34 years in this tradition, diversifying my work by auctioning sluice gates and fishing. My parents dedicated 70-80 years to this trade, making our family’s combined experience span over a century. Without formal education or modern opportunities, we relied on our skills to make a living and sustain ourselves,” says Pravin proudly.

a“While the financial returns can be substantial, the costs and effort involved are quite high. We hire divers for maintenance and repairs of the set-up, and sourcing quality materials like ‘maddi’ from distant locations is expensive. Additionally, maintaining boats and fishing nets demands constant attention and labour,” explains Pravin. Despite these obstacles, they take pride in the good fish they catch, especially during the monsoon and Diwali seasons.

One of the greatest challenges they face is environmental degradation. Rivers once teeming with life are now polluted, affecting fish breeding and reducing their catches. “Plastic waste, broken glass and other junk frequently entangle our nets. We have our fishing schedule of water tides. We install our net around midnight and come back and sleep for some time and then we go and remove our nets. Then we have to bring them home and clean them of waste such as plastic, weeds and other items,” he explains.

Their fishing methods and the community’s reliance on these practices have evolved over time. “Traditionally, nets were handmade, a painstaking process. Today, we use ready-made nets, although these still require regular repairs. The shift from bamboo to ‘maddi’ for setting up fishing structures is another change we’ve adapted to, to keep up with the times,” says Pravin.

Despite the hard work and challenges, the income from fishing has been just about sufficient for survival. “However, the rising costs of living make it difficult for younger generations to see a future in this trade. Many prefer pursuing professional education and more stable and comfortable jobs in offices or the government sector,” says Pravin. The Shet family, through sheer determination and love for their ancestral trade, has managed to sustain this business. They have declined offers from others wanting to take over, preferring to keep their heritage alive for as long as possible.