MAPUSA: Radha Gopal Naik, a petite woman with a quiet smile, is an unlikely symbol of tenacity and success against all odds, with her country chicken business. Rising above personal setbacks and powering through health issues, Radha has managed to provide for her five children and lift her family out of poverty.

Hailing from Assonora and born into a family of farmers, Radha faced a challenging childhood, where she couldn’t attend school and was tasked with work like herding cattle, cleaning stables and milking cows from a young age. Her life took a turn when she got married at the age of 18, and despite facing financial hardships, she managed to provide the bare necessities for her five children as her husband worked as a truck driver for a mining company.

The family’s stability took a hit when her husband lost his job, leading to financial struggles. In a desperate attempt to support the family, Radha’s husband took a bank loan of Rs 60,000 to buy a vehicle for tourist transportation. The old vehicle constantly broke down, leading to more expenses. The bank began pressuring the family to repay the loan, and even threatened to attach their house instead. When the bank seized the vehicle, Radha’s husband, unable to cope with the stress, attempted suicide. He survived the attempt, but passed away after a while.

Left with four school-going children and no income, Radha found herself in a dire situation. With the support of kind neighbours and her sister, she entered the business of selling country chicken just 12 days after her husband’s death. “I did not even have Rs 500 for my first investment, but my sister and neighbours helped me buy a batch of country fowl from the hinterlands of Dodamarg. I have now been doing this business for 30 years- the times have changed and the demand for these gaunti chickens has waned, but I still earn a decent income, selling my birds at the Mapusa, Bicholim and Vasco markets on different days,” she says.

In the midst of her entrepreneurial journey, Radha was diagnosed with a kidney ailment- she had developed large kidney stones, which had damaged the organ, requiring doctors to remove one of her kidneys. “I was asked not to do strenuous work, lift weights or go out to crowded places, but if I were to lay in bed after my surgery, my four children would have starved. I went to work after four month’s rest, during which time my friend Julie and colleagues at the market helped my family through it,” she recalls. “I’m glad I went back to work, as I am now hale and healthy- I do not think I would’ve recovered as well if I had stayed home,” she says.

Radha advocates for fair treatment from banks, especially for small businesses like hers. “It is painful when we see how banks go after poor people and small-time entrepreneurs like us for loan repayment, when millionaires and industrialists are let off the hook, after borrowing crores of rupees,” says Radha, who believes her husband, who was driven to desperation, may still be alive if not for the harassment he endured from the bank’s collection agents, for a small sum of money. She also calls for the government to support the hard-working common man, for whom a single financial setback could spell ruin for the entire family.

‘Rapid urbanisation has made gaunti chicken farming a rarity in Goa’

Free-range country chicken, known to be leaner, cleaner and healthier for consumption than mass-bred broilers, are getting more difficult to source in Goa due to rapid urbanisation, says Radha. “There is very little land available in towns to breed chicken, and I often have to travel to the hinterlands to buy my birds. Even those who have land now prefer to build rooms for rent, rather than farm poultry,” she laments, pointing out that villages also have shied away from rearing free-range chicken.

When she started out, a country fowl would fetch Rs 30 to 50, and a rooster, Rs 75 to 100. Today, she sells a small chicken for Rs 500 and a rooster, at Rs 1,000 each.

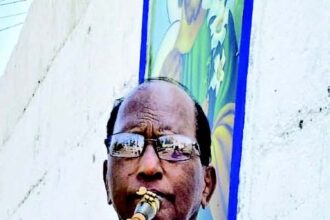

“My best customers for the roosters are Nigerians living here; they prefer the big birds. A large number of roosters are also purchased for religious beliefs and rituals- most of them are not eaten, but are released at Goa Medical College, and get to live out the rest of their days there” says Radha with a grin. Hindu patients offer roosters to their folk deities, either to pray for the release of a departed soul, or as an offering of gratitude for the recovery of a loved one at the hospital.