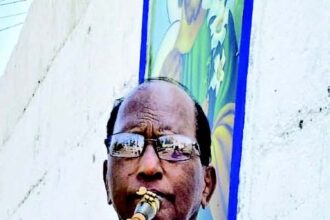

CUNCOLIM: The significance of local barbers may be lost on the younger generation, who seek the comforts of air-conditioned salons and the expertise of modern hair stylists, but people like Balu Kurtarkar have remained anchored to the old ways of barbering, refusing to change with the times. Alongside his two brothers, he carries on the family legacy of barbering, alongside another local barber who upholds this time-honoured business.

Now in his seventies, Balu recalls the early days of his career, reminiscing about how his father introduced him to the craft of cutting hair and shaving when he was just ten years old. “It was in my blood,” Balu proudly asserts, as he swiftly became an expert in the field. Over the years, Balu had the privilege of serving numerous prominent figures, including MLAs, politicians, officers, police officers, businessmen, and educators. He regales his customers with stories and experiences from the bygone era.

In the past, barbers had no fixed rates for their services. They would accept whatever payment the customer offered. If Balu provided haircuts for four or five family members, he would often receive a mere two to five rupees in compensation. Some farmers paid him in kind, offering him paddy, chillies, and occasionally vegetables, depending on the size of their families.

Traditional barbers, or mhalos, hold significant respect and importance in Hindu religion. They play a vital role in performing rituals during festivals and other occasions.

Balu is the sole mhalo who continues to carry out these sacred customs. Hindu families from Cuncolim call upon Balu for the first shave of a child’s head during the Mundan Ceremony at the age of three. They also rely on Balu to provide a clean shave after the death of a family member, usually on the fourth day following the funeral. Additionally, Balu is sought after by those performing Munj, a ritual involving the hair cutting of a son.

Interestingly, while today’s generation may prefer haircuts from barbers hailing from other States – Bihar in particular; for traditional rituals, only Balu’s services are deemed suitable, even today. Balu accepts whatever compensation the families offer for these ceremonies.

Reflecting on the changes in his profession, Balu acknowledges the introduction of electrical gadgets, expensive creams, oils, after-shave lotions, and disposable razors. “Salons have become air-conditioned establishments offering various types of massages and other luxurious amenities. In contrast, my brothers and I still operate a small, rented shop. I still remember the days when we sharpened our razors, called vakor on a leather belt and used traditional shaving soap and a unique after-shave stone called fodki,” he reminisces fondly. “In the old days, we would sit under a tree and all I needed was a small mirror and my kit, to offer haircuts and shaves. Some rich people would call us to their houses – we were not allowed to enter the house, but would offer our services in their verandahs,” he adds.

Although Balu has successfully supported his family through this profession, neither his son nor any other local mhalo in Cuncolim has shown interest in continuing his legacy. Today, Mhaleanwaddo bears only the name, devoid of any Mhale. Instead, new barbers from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Karnataka and even West Bengal have filled the void.