Fatorda: Goan furniture is undoubtedly a legacy crafted by skilled local artisans. Traditionally, Goan furniture was predominantly fashioned from wood, including bendy (Thespesia populnea), jackfruit, rosewood, and occasionally teak. Every ancestral Goan household once held a treasure trove of locally made, exquisite furniture, often masterpieces created by talented craftsmen. Unfortunately, today, many fail to appreciate the artistry of such locally crafted furniture, opting instead for more modern, comfortable pieces. Yet, in Goa, it’s not uncommon to stumble upon entire villages dedicated to carpentry, and Madel, a small village nestled in Fatorda (formerly Maddant), is one such place.

Traditionally, this village was home to skilled artisans who possessed the magical ability to transform logs of wood into exquisite household furniture.

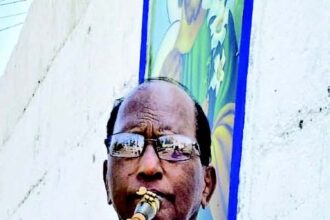

As you venture down the narrow lane near Dr Rebello’s Hospital in Madel-Pequeno, leading to Mungul, you’ll come across a quaint workshop on your right. This unassuming space belongs to Minguel D’Costa, affectionately known as Mungo by his friends and neighbours. A simple man with a warm and hospitable nature, D’Costa has been crafting furniture for households since the tender age of sixteen. After a stint abroad in pursuit of better opportunities, he returned to his homeland in the 1990’s and resumed his furniture-making business.

D’Costa specialises in crafting traditional reclining chairs or ‘easy’ chairs, locally known as ‘volters’, named after French philosopher Voltaire. D’Costa typically follows standard designs but always open to customising them to meet individual preferences. Other furniture items, like sofa sets and Planter’s chairs, are made only upon special request.

Minguel reminisces about the past when, at the age of sixteen, he crafted chairs in rosewood, selling them for a mere Rs 30 in Margão and around Rs 40 to 50 in Mapuça. Today, with the rising costs of materials and labour, the same chair, now made from bendy wood, commands a price of Rs 10,000. He crafts chairs with wooden ribbed seats and backs, as well as chairs with woven seats and backs (roteção).

In the past, he would personally weave the roteção using cane, but nowadays, it’s done with plastic twine by another artisan. D’Costa takes pride in adhering to traditional techniques by using wooden pins, called ‘torno’, for joining different parts of the chairs, without a single iron nail.

While D’Costa used to create intricately carved furniture in the past, this practice has waned. The increasing cost of carving wood, coupled with changing tastes favouring minimalism, has resulted in limited demand for carved pieces. When small carved elements are needed, he outsources the work to individuals who, regrettably, are no longer Goans.

Minguel emphasises the challenge of sourcing quality mature wood for furniture making, suggesting that planting trees suitable for furniture-making is essential for securing a future supply of premium wood.

Reflecting on the past, D’Costa notes that the pace of life was slower, and most work was labour-intensive and manual. Today, modern machinery has streamlined processes, making tasks quicker and more efficient. Despite the evolving tastes and preferences of today’s clientele, D’Costa recalls clients requesting initials and dates inscribed on the pieces he crafted for them.

Mungo expresses his concern about preserving Goa’s rich tradition of carpentry and encourages the youth to consider carpentry as a profession, taking it to new heights. He believes that doing so will not only promote and preserve Goa’s unique craftsmanship in exquisite furniture making but also provide a livelihood for future generations.