Asmita Polji

asmita@herald-goa.com

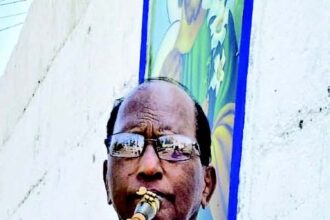

PERNEM: When he was barely 22, Dashrath Mahale, a resident of Ugvem in Pernem taluka, took to baking the quintessential Goan pao to earn his daily bread. Now 66, he continues with his business despite it not generating much profit for him and age and ailments fast catching up.

Circumstances like these would have prompted most others his age to make the most ‘practical’ decision: Shut shop and enjoy retirement. But not Dashrath. Not only has he refused to lease his baking business to the several entrepreneurs knocking on his door, but is also one of the few remaining Goan bakers who still make bread and toast in traditional wood-fired ovens that are carved deep into the walls of their homes.

Keen on keeping the passion for local baking alive, he has even volunteered to teach many Goans the ropes of the occupation. Some of these have progressed to running their own allied establishments, he proudly says.

“That’s how I started out myself,” says Dashrath as he recalls how he’d visit several major bakeries in Goa to glean the information he needed before he took up the trade himself, baking a variety of savouries until he decided to narrow down his offering to the humble Goan pao.

Goa’s local baking business has largely been taken over by migrants, a grouse that seems to be on top of Dashrath’s mind as he fights, together with his 61-year-old wife Sumitra, to keep his bakery running against the odds. Finding dedicated labourers is hard, he says, while also lamenting that none of his children are interested in taking his legacy forward. “That is probably because running a bakery is a labour-intensive job and very few youngsters in this day and age are willing to work hard to earn money,” he rues.

Another big hurdle is inflation. A truckload of wood needed to fire his oven costs anywhere between Rs. 15,000 and Rs. 20,000, but doesn’t even last a month. Dashrath explains that although the quantity of the pao that he bakes has reduced, the amount of wood required for the oven has remained the same.

“This is because the oven is required to be at a certain temperature to ensure that the bread remains soft and delicious even after it cools down. This traditional method of baking wins over electric ovens as the latter tend to only fluff up the dough, causing the finished product to harden once it cools down,” Dashrath explains.

Lack of government subsidies has also dealt a body blow to local bakers, he says. “Earlier, the state used to offer a subsidy by which bakers could purchase 90kg of flour for just Rs. 130. Now, we buy the same amount of flour for almost Rs 4,000,” he says.

The embers in his oven may be dying as demand for local pao wanes, but the embers of the Mahale couple’s willpower refuse to give up. They’d earlier use 100-200kg of maida each day to make bread. Now, this quantity has reduced to just 30-50kg. Still, they power on.

“Whatever we are today is because of our baking business. And although the next generation is not interested in it, I will continue being a baker until I am alive,” Dashrath says.