AN INDIAN EXPRESS INVESTIGATION — Published in Goa in partnership with Herald

When Journalism of Courage meets

the Voice of Goa

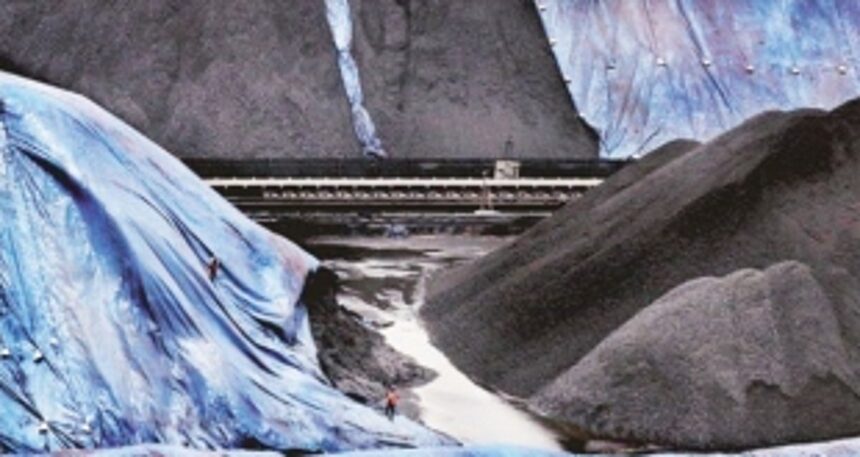

Most journeys in Goa are through a landscape straight out of picture post cards. But some of these journeys are filled with grime and soot, cutting through the swathe of Goa’s beautiful country and dotting it with black marks- the slow poison of coal pollution. A four month investigation by Indian Express left no aspect of the story of coal pollution, primarily as coal passes from Goa to steel plants across the border through different routes, untouched. And Herald was proud when Indian Express reached out to share its ‘Journalism of Courage’ with the ‘Voice of Goa’, your Herald, as its partner to publish the investigation in Goa. We present the first two parts of this investigation in todays edition of Review

— Editor

—

Nearly 25 million tonnes of coal ― evenly spread across a standard football field, this toxic black mountain will rise almost 3 km into the sky. That is the amount that will be unloaded each year at the Mormugao Port Trust by 2020, just three years away. By 2030, official records attest, this is slated to double ― up to 51.6 million tonnes each year.

In 2016-17, 12.75 million tonnes of coal was unloaded at the port and carried across Goa to power stations and refineries in Karnataka and beyond. By a clutch of importers, the biggest ones being JSW Steel Ltd and the Adani Group. And Vedanta ― together they are The Big Three ― which currently imports coal for its pig iron plant in Goa, is set to ramp up an additional 1.2 million tons of anthracite, 2.6 million tonnes of coking coal and 2.1 million tonnes of thermal coal for its proposed steel plant in Karnataka’s Bellary.

Over a four-month-long investigation, The Indian Express found that coal that arrives at the port takes three key routes, road, rail and river (see map below), that slice deep wounds in the ecological heart of the state.

The Indian Express travelled along each of these routes, following coal trucks and wagons, on a 600-km trail, to find that the transport of such huge amounts of coal is putting at risk entire habitations in villages and towns. The coal dust is blackening lungs, pushing up incidents of respiratory disorder; it’s threatening fragile forests, paddy fields, countless streams and rivers, at one place even a tiger corridor, at least two sanctuaries, and an entire hill.

Interviews with scores of residents, transporters and local administration officials and an investigation of port records show glaring gaps in the state’s regulation of this transport.

The three routes, one more coming

In villages across central Goa, men, women and children speak of how the “devil’s dust” (fine particles of coal) has changed life itself ― scarred by soot-covered homes, a lethal cocktail of respiratory ailments and a ruined ecosystem. “We take pride in being conscious of our ecological status, our beaches, our orchards, our cultivation land. Most of our youth have left the state for lack of opportunity and now when these coal corridors are being designed, there is the danger of losing our indigenous identity, too,” says Dolvyn Braganza, 25, a teacher and part-time paddy farmer and vegetable grower in Utorda.

“India comes to Goa for its vacation. This is not just our problem, this is your problem, too. Once we become a coal hub, it will be too late. Nobody likes a black Christmas,” says Braganza whose ancestral farm is located near the “coal tracks”.

Currently, official figures show that, on average , 34,200 tonnes of coal is transported each day through the rail route from Mormugao port via Vasco, Margao and Kulem into Karnataka through Hubli and Hospet.

According to the last official update, JSW and Adani transported over 3 million tonnes of coal to Karnataka through rail and a land route between April and July 2017. A second land route is being cleared and there are plans to open up a waterway through the state’s network of six rivers, with banks fashioned as coastal jetties, designed to stagger coal silos from the port towards the east.

According to official projections, each mode of transport has its own limitations, and all three need to be used together to transfer the “benefit of scale and economy”.

‘This is abuse of life’

On the other side, are people and their way of life.

Savio Correia, from Vasco, is one of the legal warriors who continues to file applications under the Right to Information Act to fight the port ― its coal plans are at the centre of a protracted battle in the courts but more of that later.

Talk to the 48-year-old about this coal trail and he describes trains that already pass near the backyard of his house in Vasco as “tarpaulin-covered graves”. “The tarpaulin covers fly against the wind. The coal they import is very fine dust, they fly across the tracks, enter our homes. If this is the kind of pollution and devastation we are facing now, what will we face with 50 million tonnes? This is abuse of life,” says Correia.

On the main road route through which trucks take coal past the 447-year-old St Andrew’s Church in Vasco town, Father Gabriel Coutinho says the coal dust can be seen on the prayer benches. “The first group of worshippers in the morning mass suffers the worst. The trucks ply in the night. By the morning, the black dust settles on the benches and the fans. When we start our prayers, switching on the ceiling fans, the coal dust spreads and falls on the worshippers. The first morning mass always begins with sneezes,” he says.

On the proposed water route, the fishing unions are the first to sound the alarm. Says Olencio Simoes, vice-chairperson, National Fishworkers’ Forum, “The dredging will collapse river beds and cause floods in neighbouring villages. Also, this will amount to violation of CRZ (Coastal Regulation Zone) norms as mangroves will be cut or destroyed along with the destruction of corals and reefs, turtle nesting grounds, horseshoe crab habitats, sea grass beds, mudflats, and nesting grounds of birds.”

Catch-22: Port needs coal

If that is the health and social cost of transport, for importers it’s cost-effective.

An investigation has found that the transport of coal is linked not only to the economics of the users but also to the future of the port itself. Indeed, it was the ban on mining and the resultant cutoff in export of iron ore ― from 43 million tonnes in 2010-2011 to 11 tonnes in 2014 ― that cleared the way for coal to come flooding into Mormugao.

During the iron-ore export days, the port contributed to 35 per cent of the state GDP, according to the Goa government . The coal that lands in Mormugao ― mainly from Australia, Indonesia and South Africa ― is currently consumed by an estimated 31 corporates.

Port records show that the Big Three have at least a berth each for themselves at the port. They show that JSW imported 10.11 million tonnes in 2016-17 for its plant in Toranagallu, Karnataka; Adani has an awarded capacity of 5.2 million tonnes for its clients in Goa, Bellary, and Hospet; and, the coal berth allotted to Vedanta has a capacity of 6.99 million tonnes, to be utilised for its proposed Bellary plant.

The Shipping Ministry, meanwhile, has identified 17 coal-backed power plants and 22 steel plants as “potential clients” in the pipeline for the Mormugao Port at Bellary, Hospet,